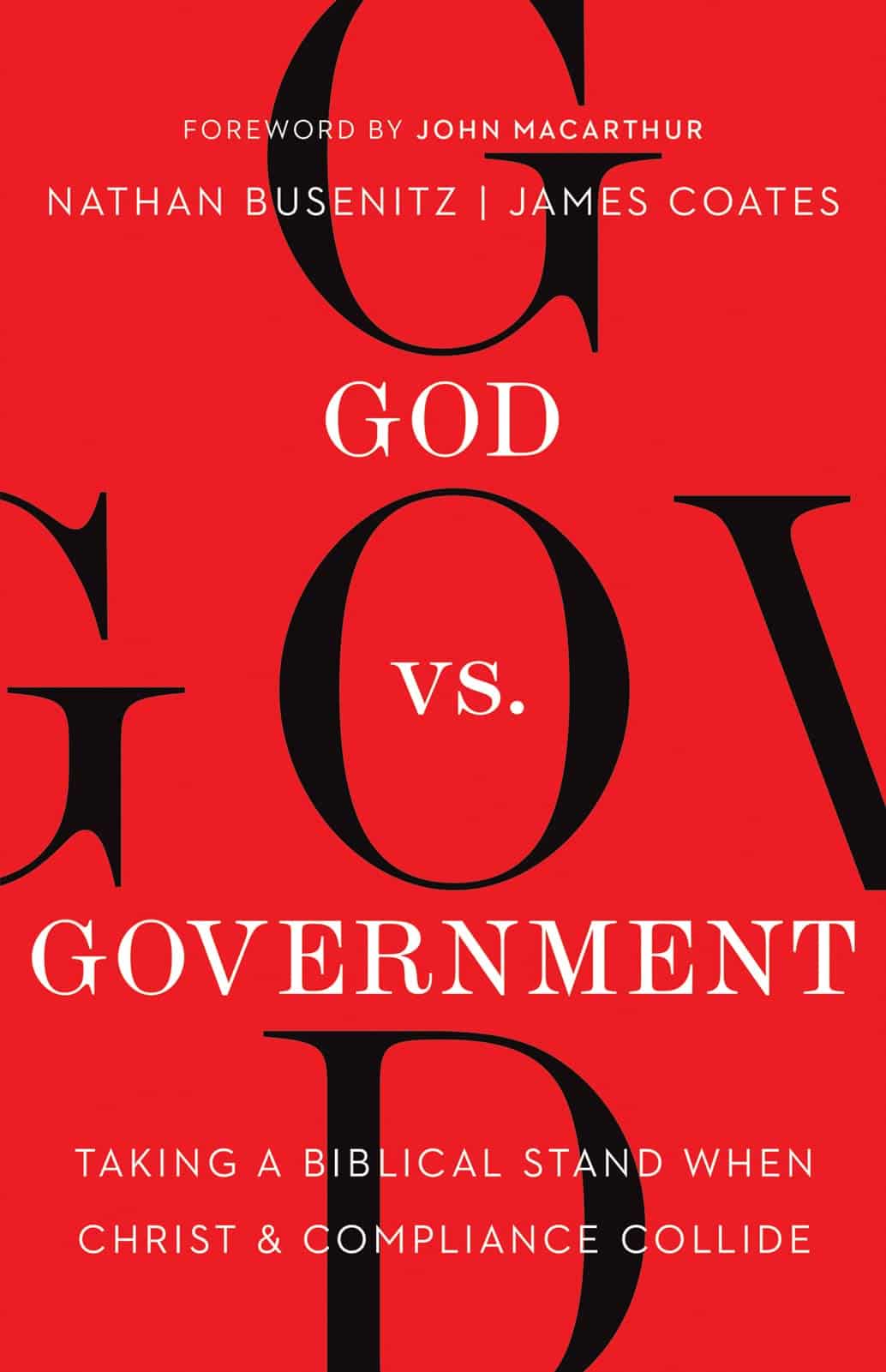

Nathan Busenitz and James Coates. God vs. Government: Taking a Biblical Stand When Christ & Compliance Collide. Eugene, OR: Harvest House, 2022. 206 pp. $17.99.

Almost no Western churches were prepared for the COVID lockdowns. Churches scrambled logistically—but even more so theologically. Because we had never before been confronted by government orders not to meet, most of us had not given adequate thought to whether we should comply with such policies. God vs. Government attempts to shore up this theological and practical deficiency. The brief book is divided into two main sections. The first (about 110 pages) is historical, as Busenitz and Coates recount the decisions of their respective churches (Grace Community Church of Los Angeles and GraceLife Church of Edmonton) to meet in defiance of local COVID restrictions.

Each church faced enormous pressure to remain closed. Grace was repeatedly assessed fines. The city of Los Angeles revoked the church’s lease on a parking lot the church had used for forty-five years. Grace pursued a variety of legal responses to these citations, eventually being vindicated and having their legal fees covered by the city.

The government’s treatment of Grace Community Church, appalling as it might be, seems merely nuisance compared to what GraceLife endured. After multiple weeks of being monitored and warned by Alberta health officials, Coates eventually submitted to imprisonment for over a month rather than committing to not meeting. The government physically barred the church from its own building, erecting temporary fencing around its property. The people of GraceLife resorted to repeatedly changing the locations of their Sunday gatherings to avoid scrutiny from health officials.

Neither ministry made a hasty decision to violate shutdown orders. Although the travails of both churches gained international media attention, the authors remind us that both churches refrained from meeting altogether for months (from mid-March until July 26) before reopening.

The second section of the book (about 80 pages) is more directly an argument for the decisions made by these assemblies. The first two chapters are short essays by Busenitz, followed by chapters that are adaptations of two sermons by Coates and one by Busenitz.

Busenitz’s first two chapters are excellent, organizing and clarifying the biblical principles in play. Happily, Busenitz does not gut the submission texts by pretending that they apply only in cases in which a government is acting righteously. He offers repeated reminders that the actual government in power when Paul and Peter urged submission was often outrageously evil and oppressive to Christianity. That said, these submission passages “should be understood in light of the men who wrote them. Their meaning must be consistent with the examples of their authors” (128). The same apostles who commanded obedience also preached in open contradiction to prohibitions and escaped from prison—the latter surely being no small matter. The second of his chapters attempts to catalog biblical examples of civil disobedience, again grouping them into categories. He then offers practical instruction for how these examples might inform our present choices.

Coates’s first sermon chapter works through texts about the necessity of the gathering of the church. There is much good here, but there is room for further exposition of the theology of our physical bodies. While there is a sense in which fellowship “is the one element of gathering that most obviously cannot be fulfilled virtually” (157), we should highlight the difference between embodied versus virtual preaching, praying, singing, and so forth. His second sermon is directed to government: a reminder to governing authorities of the God-giveness of their power and therefore of the righteous limits of that power.

The volume concludes with Busenitz’s exegesis of the most well-known verse on Christian faithfulness in the face of government opposition, Peter’s pronouncement that “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29).

One of the central arguments employed by both men is that the government and church have distinct spheres of authority. In the interest of clarity, we would do well to keep that argument separate from any judgments about the seriousness of the pandemic itself. The primary argument for maintaining the church’s gathering is that we do not recognize the validity of any government command that forbids the church to assemble for worship. As a matter of principle, we simply do not believe that such an instruction is a legitimate order from the government—full stop.

Once we affirm that, the question of whether a church should or should not meet on a given Sunday (or season) becomes a prudential question. In a weather emergency, for instance, the government might restrict all travel on the roads. As a matter of principle, we must assert that if the church refrains from meeting, it is its own prudential decision; we do not acknowledge the authority of the state to make that determination on behalf of the church.

But once we reserve that judgment for ourselves as the church, at that point we need to be able to articulate how we calculate the risks of meeting (whether that threat is meteorological or viral). Throughout God and Government, both authors offer their judgment that the threat of COVID has been greatly exaggerated. That may be a reasonable position, but we must be clear that that is not why we think that the government’s restrictions on churches were unjustified. Blurring rationales here (as the “Dear Fellow Albertans” statement does) is unhelpful.

One further critique worth suggesting here is what seems an unexamined embrace of public media to voice objections to government policies. If our goal when compelled by government is to remain faithful to God’s commands while not signaling revolution or rebellion, our use of media (whether social media, or in the case of these churches, interviews on TV and radio) demands further scrutiny.

As the COVID pandemic ends, we are now in a position to evaluate the principles on which we make our decisions without the immediate pressure of deciding what we will do this upcoming Sunday. We should take advantage of the circumstances by shoring up this aspect of our theology, and this work by Busenitz and Coates is a useful contribution to that task.

Michael Riley

Calvary Baptist Church, Wakefield, MI