Most conservative evangelicals recognize the need to separate from unbelief, false teachers, and apostasy. Paul articulates this necessity clearly in 2 Corinthians 6:14–18:

Do not be unequally yoked with unbelievers. For what partnership has righteousness with lawlessness? Or what fellowship has light with darkness? . . . Therefore go out from their midst, and be separate from them, says the Lord, and touch no unclean thing; then I will welcome you, . . .

Both as individual Christians and as churches, we must give care to distinguish ourselves and our beliefs from those who do not believe. This doesn’t mean we have no relationship with unbelievers—far from it. What it means is that we do not recognize unbelievers as Christians, and we do not partner with unbelievers in Christian ministry. The ultimate boundary of Christian unity is belief in the gospel.

Furthermore, we must separate from those who claim to be Christians, but who teach heretical doctrine. John states in 2 John 9–11:

Everyone who goes on ahead and does not abide in the teaching of Christ, does not have God. Whoever abides in the teaching has both the Father and the Son. If anyone comes to you and does not bring this teaching, do not receive him into your house or give him any greeting, for whoever greets him takes part in his wicked works.

John is clear: those who teach contrary to the teaching of Christ do not have God. Therefore, we must not “receive” these false teachers—we must not recognize them as Christians or embrace their teaching.

There can be no unity with those who do not believe the gospel; Christian fellowship is impossible with those who deny the fundamentals of the gospel, including the inerrancy of Scripture, the virgin birth, the deity of Christ, substitutionary atonement, and justification by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. The gospel is the boundary of Christian unity.

The gospel is the boundary of Christian unity.

In other words, Scripture is clear that we must not grant Christian fellowship to those who demonstrate that they are not Christian by either explicit rejection or teaching contrary to the gospel.

But What About Separating from Believers?

Separating from unbelievers, apostates, and false teachers is clear, but what about separating from other Christians?

There are two circumstances in which this kind of separation takes place. The first is when churches discipline their own members for habitual and unrepentant sin. Again, Scripture is clear on this point. Jesus himself laid out the framework for such discipline in Matthew 18:15–18, concluding,

And if he refuses to listen even to the church, let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.

Likewise, Paul commands that church members who are living in unrepentant sin should be “removed from among you” (1 Cor 5:2). This discipline is both for the spiritual benefit of the one sinning (v. 4) and also the purity and protection of other church members (v. 6).

Once again, most conservative Christians would recognize the necessity and importance of separating from unrepentant church members in this way, though unfortunately many churches do not actually practice church discipline.

Ecclesiastical Separation

However, the second circumstance in which separating from another believer takes place is the one that has likely caused the most controversy and debate, namely, what has sometimes been called “second-degree” separation—when churches and its members separate from believers or other churches/organizations that are outside their own congregation. This kind of separation occurs, not because of unbelief, heresy, or unrepentant sin, but because of serious enough theological error that would prevent ecclesiastical cooperation in certain circumstances.

The key text for this level of separation is 2 Thessalonians 3:6–15:

Now we command you, brothers, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you keep away from any brother who is walking in idleness and not in accord with the tradition that you received from us. . . . If anyone does not obey what we say in this letter, take note of that person, and have nothing to do with him, that he may be ashamed. Do not regard him as an enemy, but warn him as a brother.

Here Paul is clearly talking about something different than separating from an unbeliever or expelling a church member for unrepentant sin—note that he says at the end of verse 15 that in the case under discussion, we still treat the individual as a brother. This is different from an unbeliever, who is certainly not a brother, or an unrepentant church member, whom we are commanded to treat is if he is not a brother until he repents.

Rather, Paul’s discussion in 2 Thessalonians refers to separating from someone we still consider a Christian, but we have determined either through actions or belief are in serious enough an error that we cannot unify with them in an area of Christian cooperation.

Note that Paul says that this level of separation involves anything that is “not in accord with the tradition that you received from us.” What does that tradition involve? Paul identified it earlier in 2:15—whatever was “taught by us, either by our spoken word or by our letter.” By extension, this would include anything that does not accord with the teachings of Scripture.

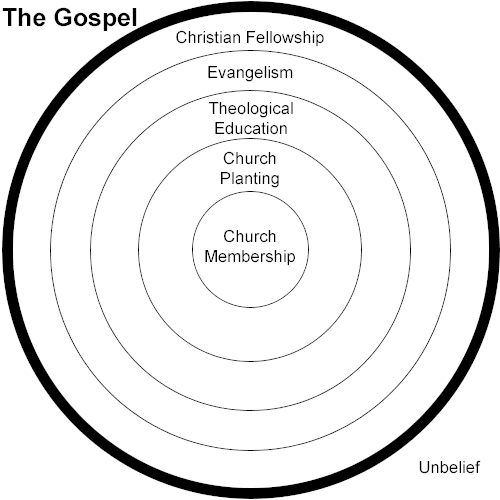

All biblical truth matters, and so all biblical truth will affect Christian unity to one degree or another. The gospel is the boundary of Christian unity—those outside the gospel are not unified with Christians in any way whatsoever, but within that boundary of the gospel, doctrinal matters like baptism, ecclesiology, hermeneutics, eschatology, and much more are still important and affect the degree to which we can unify and cooperate with other Christians.

Not All-or-Nothing Separation

What is important to recognize is that, in contrast to the other forms of biblical separation, this level of separation is not all-or-nothing. In other words, just because I believe someone is in error on a particular doctrinal matter does not mean that I can never cooperate with him in any way. The particular circumstance of Christian cooperation will affect the degree to which doctrinal disagreements will prevent unity.

For example, I may be able to stand side-by-side with a conservative Presbyterian in order to preach the gospel—we are both unified at a certain level by our common belief in the fundamentals of the gospel, but I would not be able to plant a church with him given our disagreement regarding church polity and baptism. I may be able to speak at a conference where there exists considerable diversity in a number of areas that I believe to be extremely important, but I would not be able to join a church with the same spread of divergent views.

In other words, Christian unity necessarily has two levels: unity within the boundary of the gospel, and unity centered on other important biblical doctrines and practices. The more agreement I have with someone in these other matters, the more unity I can have with him. Conversely, just because I might affirm that someone is a Christian who is inside the boundary of the gospel does not mean that I will be able to unify with him on every level. Disagreement over other “secondary” doctrines necessarily affects levels of Christian unity and cooperation, especially church planting and church membership.

Levels of Christian Unity

Of course, the challenge becomes deciding which doctrines will affect a given level of unity. Something like the identity of the “sons of God” in Genesis 6 shouldn’t affect any Christian unity; but what levels of unity will important doctrines like eschatology, ecclesiology, baptism, and soteriology affect? The important point here is that, while it might be challenging to decide where these doctrines fall in their affect on Christian unity, the should affect some levels of unity, and each church will need to decide the degree to which they will. The alternative is an unhealthy doctrinal minimalism that doesn’t consider any doctrines really important beyond the gospel.

Will the Fundamentalists Win?

This recognition of the boundary and center of Christian unity was the genius of the idea of fundamentalism that emerged in the early twentieth century in its battle with liberalism. Men like R. A. Torry, B. B. Warfield, and later J. Gresham Machen insisted that liberal Christianity was not Christianity at all since it denied fundamental tenets of the gospel such as the inerrancy of Scripture and the virgin birth. They argued that these fundamental truths of the gospel were the boundary of Christianity unity, and those who did not affirm them must not be recognized as Christian.

Liberals like Harry Emerson Fosdick decried this sort of “fundamentalism” that stressed the necessity of Christian unity being defined by fundamental doctrines. They claimed that the virgin birth, the inerrancy of Scripture, substitutionary atonement, and the bodily return of Christ must not be impediments to Christian unity. Fosdick insisted on “a spirit of tolerance and Christian liberty” concerning these issues, insisting that we should be ashamed “that the Christian Church should be quarreling over little matters when the world is dying of great needs.”1“Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”

Early fundamentalists argued that these doctrines were not “little matters”; rather, they were the very defining doctrines of biblical Christianity and therefore the necessary boundary of Christian unity. As Kevin Bauder notes, “Fundamentalists believe that separation from apostates is essential to the integrity of the gospel.”2Andrew David Naselli and Collin Hansen, eds., Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 40.

But furthermore, early fundamentalists also insisted that doctrines beyond these gospel fundamentals matter and affect unity and cooperation among those inside the boundary of the gospel. Unity among Christians, as illustrated above with church planting and church membership, will be dependent upon the level to which Christians agree in other important matters of doctrine and practice.

Another way to say it is this: agreement on the gospel creates minimal Christian unity, whereas maximal Christian unity happens the more Christians agree on the whole counsel of God. Various hyper-fundamentalist movements have perhaps notoriously made too big a deal of some issues and too little of others, but the underlying conviction that all biblical truth matters and affects unity to one degree or another is rooted in the idea that the center of Christian unity is the whole counsel of God.

Agreement on the gospel creates minimal Christian unity, whereas maximal Christian unity happens the more Christians agree on the whole counsel of God.

Gospel Minimalism

Some evangelical attempts to unify exclusively around the gospel have minimized any other doctrines they deem as secondary to the gospel, insisting that these “non-essentials” must never affect Christian unity. Doctrines like views of gender roles, personal holiness, the sufficiency of Scripture, or reverent worship are considered divisive and a hindrance to Christian unity and gospel proclamation.

The danger in this is that if we consider no doctrines beyond the gospel important, eventually lack of clarity on those doctrines will weaken the gospel itself.3Ironically, even groups like Together for the Gospel recognized this, which in their founding documents they included important doctrines like complementarianism and Lordship salvation as essential … Continue reading

So what happens when evangelicals like this minimize important doctrines, doctrines that may not be “essential” to the gospel but are nonetheless part of the whole counsel of God? The inevitable result must be that those who hold to these important secondary doctrines will not be able to cooperate on some level with those who do not. If there is lack of unity on these doctrines, how can there be unity in activities like church planting and church membership?

Thankfully, many faithful pastors today are standing up against this kind of doctrinal and practical minimalism. They are rejecting the pragmatic assimilation of the world that the Mega-church Movement promotes. Many are recovering and defending the doctrines mentioned above and are preaching on holiness and separation from the world.

And, not surprisingly, these same men are being charged with being “fundamentalists,” which has become a convenient boogieman for people who don’t know what it means.

But if fundamentalist means one who believes that doctrines essential to the gospel are the boundary of Christianity unity, and other important biblical doctrines will necessarily affect unity on other levels, then I will happily be called a fundamentalist.

References

| 1 | “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” |

|---|---|

| 2 | Andrew David Naselli and Collin Hansen, eds., Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 40. |

| 3 | Ironically, even groups like Together for the Gospel recognized this, which in their founding documents they included important doctrines like complementarianism and Lordship salvation as essential to the gospel, even though those doctrines are not really part of the gospel itself. I absolutely agree with them that weakening complementarianism and Lordship salvation will weaken the gospel, but to insist that they were only unifying around the gospel itself was actually not the case. |