God clearly wants Christians to be unified, and Christians should pursue unity wherever possible. Jesus expressed this in his high priestly prayer of John 17. He said in verse 21, “That they may all be one, just as you, Father, are in me, and I in you, that they also may be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me.”

Yet many evangelicals today champion a particular idea of Christian unity that has two problematic results: (1) lack of separation from the world, and (2) a minimization of important biblical doctrines that are deemed not to be “essential” to the gospel.

This is why it is important to recognize the nature of the unity for which Christ is praying. Thankfully, Christ’s own statements in his prayer clarify what Christian unity will look like. In verse 14, he says,

I have given them your Word, and the world has hated them because they are not of the world, just as I am not of the world.

Whatever this unity is—this unity that will make Christ known to the world—it is a unity that separates us from the world. Christ says that our beliefs in his Word will actually cause the world to hate us; our unity with him and his Word will set us apart from the world. Christ says that believers are sanctified—“set apart”—from the world by the truth of his Word:

Sanctify them in the truth; your Word is truth. As you sent me in the world, so I have sent them into the world. And for their sake I consecrate myself, that they also may be sanctified in truth. (Jn 17:17)

Christian unity is not, as many practice today, a minimization of doctrine so that we can all get along and reach the world. On the contrary, our unity that will reach the world is based on being distinct from the world and set apart by the truth of the Word.

In any discussion of Christian unity we must remember this: unity is possible only around truth, and unity around truth will make the world hate us.

Unity is possible only around truth, and unity around truth will make the world hate us.

Boundary and Center

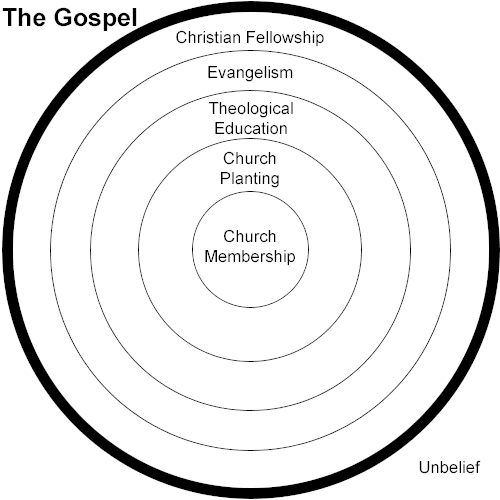

What this means, then, is that there is a boundary around Christian unity. There can be no unity with those who do not believe the gospel; Christian fellowship is impossible with those who deny the fundamentals of the gospel, including the inerrancy of Scripture, the virgin birth, the deity of Christ, substitutionary atonement, and justification by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. This is what John emphasized in his second epistle, when he wrote, “If anyone comes to you and does not bring this teaching, do not receive him into your house or give him any greeting, for whoever greets him takes part in his wicked works” (2 Jn 1:10). The gospel is the boundary of Christian unity.

The gospel is the boundary of Christian unity.

Over the last fifteen years or so, conservative evangelicals have talked a lot about the gospel as the center of Christian unity—it is what bring us together; it is what we unite around. All other doctrinal issues should be set aside, they say, in order for us to be unified around what is really important—the gospel.

But this thinking actually has it backward. Contrary to these popular evangelical movements, the gospel is not the center of Christian unity; the gospel is the boundary of Christian unity. The gospel does unify believers, but it does so in that it separates us from those who do not believe the gospel.

The center of Christian unity is the truth of God’s Word—all of it. The gospel is the boundary of Christian unity, but the center of Christian unity is the whole counsel of God, all of the truth contained in his inspired, inerrant, authoritative, and sufficient Word.

All of God’s truth matters; all of God’s truth affects Christian unity to one degree or another. The Christian faith is more than just the gospel—it is the whole council of God. Doctrinal matters beyond the fundamentals of the gospel like baptism, ecclesiology, hermeneutics, eschatology, and so much more are secondary to the gospel—they’re not the boundary—but they are important and affect the degree to which we can unify and cooperate with other Christians.

For example, I might be able to stand side-by-side with a conservative Presbyterian in order to preach the gospel—we are both unified at a certain level by our common belief in the fundamentals of the gospel, but I would not be able to plant a church with him given our disagreement regarding church polity and baptism. I may be able to teach in an educational institution where there exists considerable diversity in a number of areas that I believe to be extremely important, but I would not be able to join a church with the same spread of divergent views.

In other words, Christian unity necessarily has two levels: unity within the boundary of the gospel, and unity centered on other important biblical doctrines and practices. The more agreement I have with someone in these other matters, the more unity I can have with him. Conversely, just because I might affirm that someone is a Christian who is inside the boundary of the gospel does not mean that I will be able to unify with him on every level. Disagreements over other “secondary” doctrines necessarily affect levels of Christian unity and cooperation, especially church planting and church membership.

Levels of Christian Unity

Of course, the challenge becomes deciding which doctrines will affect a given level of unity. Something like the identity of the “sons of God” in Genesis 6 shouldn’t affect any Christian unity; but what levels of unity will important doctrines like eschatology, ecclesiology, baptism, and soteriology affect? The important point here is that, while it might be challenging to decide where these doctrines fall in their affect on Christian unity, they should affect some levels of unity, and each church will need to decide the degree to which they will. The alternative is an unhealthy doctrinal minimalism that doesn’t consider any doctrines really important beyond the gospel.

Will the Fundamentalists Win?

This recognition of the boundary and center of Christian unity was the genius of the idea of fundamentalism that emerged in the early twentieth century in its battle with liberalism. Men like R. A. Torry, B. B. Warfield, and later J. Gresham Machen insisted that liberal Christianity was not Christianity at all since it denied fundamental tenets of the gospel such as the inerrancy of Scripture and the virgin birth. They argued that these fundamental truths of the gospel were the boundary of Christianity unity, and those who did not affirm them must not be recognized as Christian.

Liberals like Harry Emerson Fosdick decried this sort of “fundamentalism” that stressed the necessity of Christian unity being defined by fundamental doctrines. They claimed that the virgin birth, the inerrancy of Scripture, substitutionary atonement, and the bodily return of Christ must not be impediments to Christian unity. Fosdick insisted on “a spirit of tolerance and Christian liberty” concerning these issues, insisting that we should be ashamed “that the Christian Church should be quarreling over little matters when the world is dying of great needs.”1“Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”

Early fundamentalists argued that these doctrines were not “little matters”; rather, they were the very defining doctrines of biblical Christianity and therefore the necessary boundary of Christian unity. As Kevin Bauder notes, “Fundamentalists believe that separation from apostates is essential to the integrity of the gospel.”2Andrew David Naselli and Collin Hansen, eds., Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 40.

But furthermore, early fundamentalists also insisted that doctrines beyond these gospel fundamentals matter and affect unity and cooperation among those inside the boundary of the gospel. Unity among Christians, as illustrated above with church planting and church membership, will be dependent upon the level to which Christians agree in other important matters of doctrine and practice.

Another way to say it is this: agreement on the gospel creates minimal Christian unity, whereas maximal Christian unity happens the more Christians agree on the whole counsel of God. Various hyper-fundamentalist movements have perhaps notoriously made too big a deal of some issues and too little of others, but the underlying conviction that all biblical truth matters and affects unity to one degree or another is rooted in the idea that the center of Christian unity is the whole counsel of God.

Agreement on the gospel creates minimal Christian unity, whereas maximal Christian unity happens the more Christians agree on the whole counsel of God.

Do Not Love the World

The danger of forgetting this important biblical definition of Christian unity is a sort of doctrinal minimalism that tends to downplay both the necessity of separation from the world and unity around all of God’s truth, both of which will inevitably weaken the gospel itself.

On the one hand, often in a noble attempt to unify around the gospel in order to reach the world, many evangelicals have forgotten the importance of separation from the world, instead attempting to be as much like the world as possible as a means to reach the world. They assume that in order to reach the world, we need to be liked by the world, forgetting that Jesus himself said that unity around his truth would cause the world to hate us.

This lack of separation from the world inevitably leads to dissolving the boundary of Christian unity—the gospel. Iain Murray argues that this is a serious problem for Evangelicals:

Apostasy generally arises in the church just because this danger ceases to be observed. The consequence is that spiritual warfare gives way to spiritual pacifism, and, in the same spirit, the church devises ways to present the gospel which will neutralize any offense. The antithesis between regenerate and unregenerate is passed over and it is supposed that the interests and ambitions of the unconverted can somehow be harnessed to win their approval for Christ. Then when this approach achieves “results”—as it will—no more justification is thought to be needed. The rule of Scripture has given place to pragmatism.3Iain H. Murray, Evangelicalism Divided: A Record of Crucial Change in the Years 1950 to 2000 (Carlisle, PA: Banner of truth, 2000), 255.

This agenda can be still clearly seen in many evangelical churches today. Murray notes,

That this has happened on a large scale in the later-twentieth century is to be seen in the way in which the interests and priorities of contemporary culture have come to be mirrored in the churches. The antipathy to authority and to discipline; the cry for entertainment by the visual image rather than by the words of Scripture; the appeal of the spectacular; the rise of feminism; the readiness to identify power with numbers; the unwillingness to make ‘beliefs’ a matter of controversy—all these features so evident in the world’s agenda are now also to be found in the Christian scene. Instead of churches revolutionizing the culture the reverse has happened. Churches have been converted to the world.4Murray, Evangelicalism Divided, 255–6.

If our central goal is to gain the world’s approval, we will inevitably lose our focus on the truth of God’s Word. That this happened in Evangelicalism is without question. One of first doctrines to go was inerrancy, followed soon by justification by faith alone in Christ alone (evidenced by controversies like the New Perspective on Paul) and the omniscience of God (evidenced by Open Theism).

On the other hand, some evangelical attempts to unify exclusively around the gospel have minimized any other doctrines they deem as secondary to the gospel, insisting that these “non-essentials” must never affect Christian unity. Doctrines like a complementarian view of gender roles, personal holiness, the sufficiency of Scripture, or reverent worship are considered divisive and a hindrance to Christian unity and gospel proclamation.

Again, the danger in this is that if we consider no doctrines beyond the gospel important, eventually lack of clarity on those doctrines will weaken the gospel itself.5Ironically, even groups like Together for the Gospel recognized this, which in their founding documents they included important doctrines like complementarianism and Lordship salvation as essential … Continue reading

So what happens when evangelicals like this minimize important doctrines, doctrines that may not be “essential” to the gospel but are nonetheless part of the whole counsel of God? The inevitable result must be that those who hold to these important secondary doctrines will not be able to cooperate on some level with those who do not. If there is lack of unity on these doctrines, how can there be unity in activities like church planting and church membership?

Thankfully, many faithful pastors today are standing up against this kind of doctrinal and practical minimalism. They are rejecting the pragmatic assimilation of the world that the Mega-church Movement promotes. Many are recovering and defending the doctrines mentioned above and are preaching on holiness and separation from the world.

And, not surprisingly, these same men are being charged with being “fundamentalists,” which has become a convenient boogieman for people who don’t know what it means.

But if fundamentalist means one who believes that doctrines essential to the gospel are the boundary of Christianity unity, and other important biblical doctrines will necessarily affect unity on other levels, then I will happily be called a fundamentalist.

True Christian Unity

True Christian unity can be achieved only by the truth of God’s Word, within the boundaries of gospel essentials, and centered in the whole council of God. Minimization of any of God’s truth inevitably leads to the erosion of doctrine and the ultimate dissolution of true Christian unity.

References

| 1 | “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” |

|---|---|

| 2 | Andrew David Naselli and Collin Hansen, eds., Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 40. |

| 3 | Iain H. Murray, Evangelicalism Divided: A Record of Crucial Change in the Years 1950 to 2000 (Carlisle, PA: Banner of truth, 2000), 255. |

| 4 | Murray, Evangelicalism Divided, 255–6. |

| 5 | Ironically, even groups like Together for the Gospel recognized this, which in their founding documents they included important doctrines like complementarianism and Lordship salvation as essential to the gospel, even though those doctrines are not really part of the gospel itself. I absolutely agree with them that weakening complementarianism and Lordship salvation will weaken the gospel, but to insist that they were only unifying around the gospel itself was actually not the case. |