Author Robert Morgan calls William Cowper (1731–1800) “one of God’s gracious gifts to those suffering from depression” (Then Sings My Soul, 69). Cowper (pronounced “Cooper”) led a life of pain, grief, disappointment and suffering. In his darkest moments, he believed that God had utterly rejected him, and Cowper attempted suicide on several occasions. But when he was thinking clearly, he gave voice to a fragile yet real faith that has provided comfort and encouragement for countless believers after him.

Cowper was born near London into the home of an Anglican minister, but not one who followed the evangelical gospel of the Wesleys and George Whitefield. Cowper’s first major taste of sorrow came at age 6, when his mother died. William’s father then sent him to a boarding school, where the quiet, reserved boy was bullied and likely abused by fellow students.

William’s father wanted his son to become a lawyer. William began studies but did not apply himself to his work. A major bout with depression in 1752 set him back, and further disappointment followed when his engagement to his cousin Theodora was called off by her father. William half-heartedly pursued a career in civil service, and in 1763 his father arranged for William to become Clerk of Journals in Parliament. But first, William faced a public examination for the position. Overwhelmed by the prospect of the interview, William fell into deep despair again, unsuccessfully attempted suicide, and eventually suffered a complete mental breakdown caused in part by his guilt over his desire to take his own life. He was sent to an insane asylum in December 1763.

What could have been a tragic end for William instead became the event that God used to draw him to saving faith. The operator of the institution was one Nathaniel Cotton, who by God’s grace was an evangelical Christian. Dr. Cotton took a special interest in this unusual patient, and provided a Bible for William to read. Through God’s Word and His servant Dr. Cotton, William came to understand the hope of eternal salvation through the death and resurrection of Christ—for him. William placed his faith in Christ for salvation in early 1764. Overwhelmed now with gratitude, William lived for another year at the asylum, growing in his newfound faith.

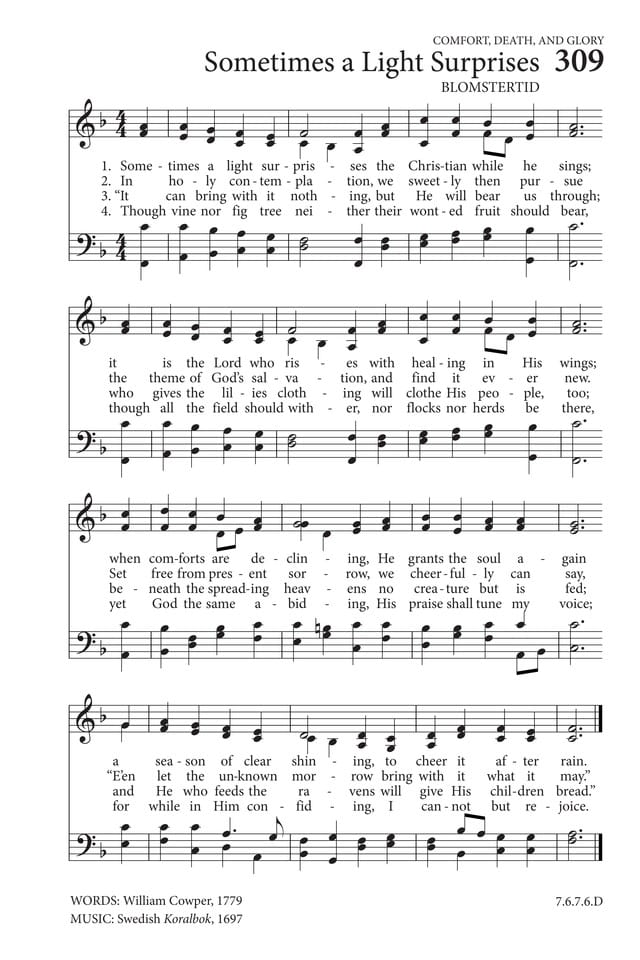

In 1765 William went to live with Morley and Mary Unwin, a Christian couple who provided William with rest and respite. Tragedy struck again in 1767 when Morley died following a fall from a horse. Mary and William then moved to nearby Olney where they began attending a church pastored by a dynamic preacher who had been saved from a life of sin and debauchery and never got over the amazing grace God had extended to him. John Newton, whom John Piper calls “one of the healthiest men in the eighteenth century” (The Hidden Smile of God, p. 84), had pastored in Olney for several years by the time William Cowper moved into town. As had Dr. Cotton, Newton also took a particular interest in Cowper, meeting with him frequently, taking William along on visitation calls, and encouraging William to develop hobbies—particularly writing poetry. Newton proposed that he and Cowper compile a hymnal. Newton had developed the habit of writing poems to accompany his sermons, and upon discovering his new friend’s poetic gifts, felt that Cowper had a depth of skill and insight to contribute. The result, Olney Hymns (1779), became the world’s introduction to Newton’s classic hymns “Amazing Grace” and “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken,” as well as Cowper’s powerful texts on the sovereignty of God, “God Moves in a Mysterious Way” and “Sometimes a Light Surprises.”

William’s years at Olney were some of the happiest of his life. When Newton became involved in the effort to abolish the British slave trade, he partnered with Parliament member William Wilberforce to arouse public sentiment against the practice. Cowper contributed too, with his powerful poem “Pity for Poor Africans,” which still speaks piercingly against those who would make excuses for joining in with wickedness. Pastor, politician and poet combined efforts to address the evils of the slave trade, eventually leading to its abolishment in England in 1807.

In 1780, a year after the publication of Olney Hymns, John Newton left Olney for a pastorate in London. While William struggled with the departure of his friend and mentor, he also worked on poems that would cement his place as one of the major English poets of the day. In particular, his long poem The Task and his translation of Homer gained widespread praise and have continued to be studied.

But William was never far from depression. His final poem, “The Castaway,” (1799) describes a sailor swept overboard in a storm at sea. But the poem is not just about a nameless sailor lost in the ocean—William concludes with the miserable lines, “But I beneath a rougher sea,/And whelm’d in deeper gulfs than he.”

What was William Cowper’s spiritual state? While the bleakness of his despair might point to a lack of true saving faith, it is reported that on his deathbed his hopeless countenance suddenly lit up, as if realizing, “I am not shut out of heaven after all!”1As with much of hymn history, this quote is difficult to substantiate. Smith and Carlson attribute it to a book by Reuben Halleck, where it does not seem to appear. Similarly, another online source … Continue reading Perhaps a better testimony comes from Cowper’s hymns. In his most famous hymn, “There Is a Fountain” he writes, “The dying thief rejoiced to see that fountain in his day/And there may I, though vile as he, wash all my sins away.” For Cowper, this was no hyperbole.

Even more beautiful is Cowper’s account of his conversion. After reading Romans 3:25, he recounted, “Immediately I received the strength to believe it, and the full beams of the Sun of Righteousness shone upon me” (Thomas, William Cowper and the Eighteenth Century, p. 108). The illuminating work of God continued in William’s life, allowing him to later write:

Sometimes a light surprises the Christian while he sings;

It is the Lord, who rises with healing in His wings:

When comforts are declining, He grants the soul again

A season of clear shining, to cheer it after rain.

In holy contemplation we sweetly then pursue

The theme of God’s salvation, and find it ever new.

Set free from present sorrow, we cheerfully can say,

“Let the unknown tomorrow bring with it what it may.”

It can bring with it nothing but He will bear us through;

Who gives the lilies clothing will clothe His people, too;

Beneath the spreading heavens, no creature but is fed;

And He who feeds the ravens will give His children bread.

Though vine nor fig tree neither their wonted fruit should bear,

Though all the field should wither, nor flocks nor herds be there;

Yet God the same abiding, His praise shall tune my voice,

For while in Him confiding, I cannot but rejoice.

—William Cowper, 1779

This text has been stunningly set to music in a choral piece by Craig Courtney. The use of mixed meter and dissonance, not to mention an ending that does not quite resolve, beautifully illustrate the text but make the tune somewhat difficult to use congregationally. For congregational use, the little-known Swedish tune BLOMSTERTID provides a singable way for God’s people to appropriate Cowper’s words of hopeful faith arising from suffering.

References

| 1 | As with much of hymn history, this quote is difficult to substantiate. Smith and Carlson attribute it to a book by Reuben Halleck, where it does not seem to appear. Similarly, another online source cites John Julian’s Dictionary of Hymnology, which speaks of a change of countenance at death but does not contain this quote. |

|---|