GDJT 2 (2023): 1–43

Download PDF

Several NT texts present a strong contrast between believers and the world.[2] “I chose you out of the world, therefore the world hates you” (John 15:19).[3] “Do not be conformed to this world” (Rom 12:2a). “You were dead in the trespasses and sins in which you once walked, following the course of this world” (Eph 2:1–2). “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God the Father is . . . to keep oneself unstained from the world” (Jas 1:27). “Whoever wishes to be a friend of the world makes himself an enemy of God” (Jas 4:4). “Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him” (1 John 2:15). “Do not be surprised, brothers, if the world hates you” (1 John 3:13). Such texts undeniably play a significant role in the theology of the NT and in the life of the church.[4]

The church, however, has failed to adequately teach and apply the biblical teaching on “the world” with the result that evangelical churches have become too much like the world.[5] This failure to correctly understand the church’s relationship with the world is primarily a theological, rather than a sociological, issue.[6] A well-developed biblical theology of the world is lacking in scholarly literature. Theological literature that does address the topic of the world focuses almost entirely on NT texts and rarely addresses the OT development of the theological concept of the world in a meaningful way. Generally, these studies point out some cosmological references to creation in the OT and then move on to NT texts,[7] giving the impression that the NT is suddenly introducing a new concept when it distinguishes believers from the world. A few studies correctly discuss the OT conceptual foundation for the NT concept of the world as describing sinful humanity in opposition to God.[8] These studies, however, are brief and do not thoroughly develop the OT background. Two of these works (correctly) draw a connection between the OT contrast of “the nations” in opposition to Israel and the NT contrast of “the world” in opposition to “the church.”[9] Apart from these few exceptions, this connection between “the nations” in the OT and “the world” in the NT has gone almost entirely unnoticed in scholarly literature.[10] In examining the biblical data, however, the relationship between “the nations” and “the world” is striking. Some NT authors initially adapt OT terminology referring to “the nations” (or “the Gentiles”) in contrast to the people of God but other NT authors begin discussing this concept by referring to the contrast between the people of God and the world.

This paper will first summarize the OT usage of the concept of “the nations” in contrast to Israel; this paper will then examine how some NT authors refer to “the nations” or “the Gentiles” to speak of the contrast between believers and sinful humanity, while other NT authors refer to “the world” to refer to this same distinction. When analyzing the way the different NT authors use these terms, (1) there is significant overlap in meaning and (2) the concepts spoken of in relation to these terms are close parallels to the OT presentation of the distinction between Israel and the nations. The NT concept of the world in contrast to the church represents the progressive development of the OT concept of the nations in contrast to Israel. This understanding of the OT foundation for the NT concept of the world will provide a strong theological foundation for a more thorough understanding of the church’s relationship with the world.

Israel and the Nations in the Old Testament

The post-fall narrative of Genesis begins with the development of two contrasting seed lines originating from the promise in Genesis 3:15.[11] One of the seed lines includes Seth, Noah, and Shem, and represents the royal lineage that will lead ultimately to the coming Messiah.[12] After the scattering of people into various nations after the Babel event (Gen 10–11), God chooses Abraham out from among those nations to be the progenitor of a great nation through whom God will bless all the nations of the earth (Gen 12:1–3). From this point forward, much of the conflict in the plot line of the OT narrative focuses on the relationship between Abraham’s offspring and the surrounding nations. Israel’s identity in its relationship with Yahweh is reflected in its relationship to the other nations.

The OT uses two key terms to refer to peoples (עַם) and nations (גֹּוי). The terms are often used in a generic, non-theological sense, but the OT often uses plural forms of both גֹּוי (foreign, often pagan, nations) andעַם (“peoples”) to refer to the other nations in contrast to Israel. The former more often carries the sense of “nations” whereas the latter often refers to “families” though they are mostly interchangeable. It seems that “עַם rather stresses the blood relationship, often hardly different” than גֹּוי, which often refers to pagans or “the heathen” (e.g., Exod 34:24; Lev 18:24).[13] The early patriarchal promises refer to the influence of Abraham’s descendants over both “nations” (use of גֹּוי in Gen 17:4,5,16; 25:23; and 35:11) and “peoples” (use of עַם in Gen 17:16; 27:29; 28:3; 48:4; 49:10). The OT uses גֹּוי in a plural form 427 times and עַם in a plural form 240 times.[14] Alexander proposes a subtle distinction between the two terms: “Whereas the latter [עַם] merely designates a group of human beings having something in common, the former [גֹּוי] denotes a group of people inhabiting a specific geographical location and forming a political unit.”[15] It is noteworthy, though, that the OT frequently uses these terms as essentially synonymous technical terms for the unbelieving, pagan peoples in the surrounding nations in contrast to Yahweh’s holy גֹּוי, Israel (Exod 19:6). Israel is his “treasured possession among all ‘peoples’” (19:5). In this sense, Israel functions as the visible people of God, whereas the nations/the peoples function as the collective group of unbelievers opposed to Yahweh and his people. It is readily acknowledged that not all ethnic Israelites were truly devoted to Yahweh and that non-Israelites were able to exercise saving faith and become the people of Yahweh.[16] The OT routinely uses the term “the nations” to refer to those (predominantly Gentiles) who are set in contrast to the visible people of God. When reviewing the references to the peoples and the nations in contrast to Israel in the OT, four key themes emerge: (1) Yahweh’s people as distinct from the nations, (2) Yahweh’s promise to bless the nations through his people, (3) being distinct from the peculiarly sinful ways of the nation, and (4) judgment on the nations.

Yahweh’s People as Distinct from the Nations

God’s call of Abraham and his offspring in Genesis marks them out as a nation distinct from the other nations. In Exodus, Yahweh delivers Jacob’s descendants from bondage in order to lead them to the Promised Land, where they will be surrounded by pagan nations. Yahweh constitutes Israel as a nation and presents her “mission statement” (Exod 19:4–6).[17] Israel is his “treasured possession among all peoples” (19:5). The idea here is that Yahweh maintains a special relationship with Israel that he does not have with other nations.[18] Yahweh then declares Israel’s role as a “kingdom of priests” and a “holy nation.” Both of these terms are critical in understanding Israel’s identity as God’s people among the other nations. As a kingdom of priests, Israel is to serve ontologically and functionally as mediators of the knowledge of God to the pagan nations.[19] Israel, then, should be “committed to the extension throughout the world of the ministry of Yahweh’s presence.”[20] As the Levitical priests of Israel were to display the holiness of Yahweh and to make him known to Israel, so Israel should display the holiness of Yahweh and make him known to the nations (cf. Deut 4:5–9).

The third description of Israel is that of a “holy nation.”[21] Some interpreters assert that the phrases “holy nation” and “kingdom of priests” are virtually synonymous.[22] Kaiser, however, argues correctly that the phrases are not synonymous.[23] “Kingdom of priests” refers to Israel’s role in her ministry to the surrounding nations; “holy nation”[24] refers to Israel’s responsibility toward Yahweh to be distinct from the other nations in behavior and worship. The significance of the coupling of these phrases is that the mission of Israel is to bring the nations to Yahweh, but while carrying out this mission, it is essential for them to be distinct from the nations in their theology and lifestyle. Though the suggested etymology of קדשׁ meaning “to cut/separate” may or may not be relevant to the meaning of the word, most interpreters agree that the concept of “separateness” is fundamental to the meaning of holiness, or at least a “necessary consequence”[25] when referring to both divine and human holiness.[26] Holiness refers to God’s incomparable greatness in that he is set apart from all else in his transcendence (Exod 15:11–12; 19:10–25; Isa 6:1–4; 57:15), and human holiness refers to people being set apart from sin and to God. God’s command to be holy in Leviticus 20:26 is based on the fact that he “separated” (בּדל) them from the peoples. Separateness is an element of holiness, but as a kingdom of priests serving the other nations, Israel cannot be separate in a spatial sense. Thus, separateness or distinctiveness in both religion and lifestyle best captures the meaning of “holiness” for Israel. God’s command for Israel to be a kingdom of priests and a holy nation means that in their priestly role they are to minister to the other nations and bring them to a knowledge of Yahweh. In their role as a “holy nation,” however, they are to remain distinct from the behavior and worship of the other nations.

The rest of the OT continues to refer to Israel’s special status as distinct from the nations. Though Israel will occupy land in the midst of other nations, Yahweh has separated Israel from “the peoples” (Lev 20:24, 26; 1 Kgs 8:53). Israel is Yahweh’s “treasured possession, out of all the peoples who are on the face of the earth,” though they were the “fewest of all peoples” (Deut 7:6–7; cf. 14:2). Yahweh “set his heart in love on your fathers and chose their offspring after them, you above all peoples” (Deut 10:15). This distinction from the nations results in conflict with the nations. The surrounding nations serve their own gods and have little interest in Yahweh. Israel struggles to be faithful to Yahweh and, rather than ministering to the other nations, becomes like the other nations and serves their gods. From the time Israel becomes a nation in Exodus until the close of the Old Testament period, violent enmity persists between Israel and the surrounding nations. The animosity of the nations toward Israel is prominent in the Psalms (79:1–13; 80:6; 83:1–4; 89:50–51) and in the Prophets (Mic 4:11–5:1; Joel 1:6; Jer 1:14–16; 10:25; Ezek 36:3; Zech 12:3; 14:2–3). It is difficult to find an extended period of time when Israel is at peace with the nations.

Yahweh’s Promise to Bless the Nations through His People

A central promise of the OT is the promise of blessing to the nations. Through Abraham and his offspring, God promises to bless “all the families of the earth” (Gen 12:3; 28:14) and “the nations” (גֹּוי in Gen. 18:18; 22:18; 26:4). Andreas J. Köstenberger points out that this idea of salvation for the nations is “already implicit in the protevangelion of Genesis 3:15 (which predates the call of Abraham) and is made explicit in the blessing associated with Abraham (12:3) and his seed (22:18).”[27] A primary aspect of the blessing on the nations appears to include the fact that the other nations will serve Abraham’s offspring (Gen 24:60; 27:29; 49:10). This authority over the nations, however, results not in enslaving those nations but in blessing them (22:17–18). These promises indicate that the offspring of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob will maintain a distinctive position among the other nations. Israel can be a blessing to the nations in their role as a kingdom of priests (Exod 19:6).

The OT emphasizes Yahweh’s desire for the nations to know him and to be the recipients of the blessing of Abraham. Köstenberger observes, “Despite all the nations’ detestable practices, God is concerned also for their salvation.”[28] God himself rules over the nations (Ps 22:28; 96:10), and he is exalted over the peoples (Ps 99:2). God’s people will rule over the nations (Ps 18:43; 47:8–9). Yahweh’s servant will be “a light to the nations” (Isa 49:6) and to the peoples (Isa 51:4), so that his “salvation may reach to the end of the earth” (Isa 49:6).[29] Yahweh intends for his deeds to be made known among the peoples (1 Chr 16:8; Ps 96:3; 105:1; Isa 12:4) and praised among the nations (1 Chr 16:24; Ps. 18:49). When his deeds are made known among the peoples, the nations will “be glad and sing for joy” and the peoples will praise him (Ps 67:4–5). The peoples will see his glory (Ps 97:6), and “all the families of the nations shall worship before you” (Ps 22:27; cf. 86:9). In the latter days, the temple mount will be exalted, “all the nations shall flow to it,” and many peoples will go to this mountain to learn the ways of Yahweh (Isa 2:2–3; cf. Zech 8:22). In those times, “then the nations will know that” Yahweh is the God of Israel (Ezek 37:28; 39:7).

Being Distinct from the Sinful Ways of the Nations

Yahweh’s people must not follow the practices of the nations. Because Israel must be a holy nation (Exod 19:6), the OT includes numerous warnings against following the practices of the nations. Yahweh’s people are to be distinct from the nations because the nations are characteristically sinful. After giving laws regarding uncleanness and uncovering nakedness (Lev 18:1–23), Yahweh says that it is by these things that the nations have become unclean (Lev 18:24). Israel is not to “do as they do” in Egypt or in Canaan. Instead of walking in their statutes, they must follow Yahweh’s rules and keep his statutes (Lev 18:3–5). The customs of the nations are evil. “You shall not walk in the customs of the nations that I am driving out before you, for they did all these things, and therefore I detested them” (Lev 20:23; Deut 18:9). Because the wickedness of the Canaanites is so great, God’s people must “destroy all the places where the nations whom you shall dispossess served their gods” (Deut 12:2). The idolatry of the nations is evil. “You shall not go after other gods, the gods of the peoples who are around you” (Deut 6:14). Moses warns that God’s people must resist the enticements to serve other gods, “the gods of the peoples who are around you” (Deut 13:7). Going after the gods of the peoples constitutes abandonment of Yahweh, and it provokes Yahweh to anger (Judg 2:12). This is such a serious offense to Yahweh that the penalty is death (Deut 13:9–11).

When the people enter Canaan, Yahweh allows some of these wicked nations to remain “to test Israel by them” (Judg 3:1). Israel frequently fails the test. Speaking of the time of the judges, Psalm 106 says that Israel “mixed with the nations and learned to do as they did” (Ps 106:35). They served their idols, sacrificed their children to Canaanite idols, and “became unclean by their acts and played the whore in their deeds” (Ps 106:36–39). One specific way God’s people emulate the nations is in their desire to have a king “like the nations that are around me” (Dt 17:14; 1 Sam 8:5, 20), thereby rejecting Yahweh’s rule (1 Sam 8:7–9). In Saul, Yahweh does indeed give his people a king “like the nations.”

Solomon later follows the ways of the nations by taking wives “from the nations” forbidden by God, and they turn his heart away after their gods (1 Kgs 11:2). Immediately after Solomon’s failed reign, his son Rehoboam oversees a nation that practices worship “according to all the abominations of the nations that the Lord drove out before the people of Israel” (1 Kgs 14:24). Other kings continue to follow in the ways of the nations. Ahaz “even burned his son as an offering, according to the despicable practices of the nations” (2 Kgs 16:3; 2 Chr 28:1–4). The leaders of Israel and Judah continue to follow the religious practices of the nations, and they do even more evil than the nations (2 Kgs 21:9; 2 Chr 33:9), incurring God’s judgment through exile (2 Kgs 17:8–18; 2 Kgs 21:2–16; 2 Chr 33:2–9; 36:14–21).

The injunction to resist conformity to the nations continues into the exilic period, where Yahweh says, “Learn not the way of the nations” (Jer 10:2). The specific example given here is a warning against being “dismayed at the signs of the heavens because the nations are dismayed at them.” Yahweh’s people must not learn these ways “for the customs of the peoples are vanity” (Jer 10:3). This vanity is manifested in the idolatry of the people, who will cut down a tree and worship it (Jer 10:4–5). Indeed, “the gods of the peoples are worthless idols” in contrast to Yahweh who “made the heavens” (1 Chr 16:26; Ps 96:5; 135:15–18). Instead of following Yahweh’s rules, the people act “according to the rules of the nations” around them (Ezek 11:12). Not only do Yahweh’s people follow the customs of the nations, but they do “wickedness more than the nations, and against my statutes more than the countries all around her.” Therefore, Israel is “more turbulent than the nations” (Ezek 5:6–7; cf. 16:48, 51). In this case, Israel, “has not even lived up to the standards of the nations, that is, the mores and customs of her pagan neighbors.”[30]

The theme continues in post-exilic times. Yahweh had brought his people into a land that is “impure with the impurity of the peoples of the lands, with their abominations that have filled it from end to end with their uncleanness” (Ezra 9:11). However, “the people of Israel and the priests and the Levites have not separated themselves from the peoples of the lands with their abominations” (9:1). The primary example of this is intermarriage with the pagan peoples (9:2, 14), a sin which brings greater anger from Yahweh (9:14–15). The sin was so serious that Ezra urges the people to do Yahweh’s will by separating “from the peoples of the land and from the foreign wives” (10:11).

Judgment on the Nations

Even though Yahweh desires for the nations to know him, he must judge those who reject him. Before Israel reaches the Promised Land, Yahweh promises, “I will cast out nations before you” (Exod 34:24). In Balaam’s oracle, he says that God will “eat up the nations, his adversaries, and shall break their bones in pieces and pierce them through with his arrows” (Num 24:8). The Psalms pray for judgment on the nations (Ps 9:5, 15–20; 56:7; 59:5; 79:6). Yahweh holds all the nations in derision (Ps 59:8), and “he will execute judgment among the nations, filling them with corpses” (Ps 110:6; cf. 149:7). He will come to “judge the world in righteousness and the peoples in his faithfulness” (Ps 96:13). The prophetic books also anticipate Yahweh’s judgment on the nations (Isa 30:28; 34:2–8; 63:6; Jer 25:15; 30:11; 46:28; Mic 7:17).

To summarize, the OT presents four recurring themes related to Israel’s relationship to the nations. (1) Yahweh’s purpose for Israel is for them to be distinct from the other nations in order to (2) make Yahweh known to the other nations. (3) The recurring corresponding instruction in the OT is for Israel to be distinct from the nations, and (4) Yahweh promises to judge the nations who refuse to acknowledge him. Israel frequently fails to resist the inclination to idolatry and the practices of the nations. Next, we will examine how the NT uses these same four themes when it refers to the relationship between the people of God and the mass of unbelievers.

The Nations and the World in the Gospels and Acts

This same contrast between the people of God and the nations in the OT continues in the NT. Some NT authors refer to the people of God in contrast to “the nations” in a similar way to that which the OT authors do. This is evident primarily in the Synoptic Gospels, Acts, the letters of Paul and Peter, and in Revelation.[31] The NT usage of plural ἔθνη, in particular, as well as ἐθνικός, in these writings demonstrates a continuation of the OT theme of Israel as God’s people in contrast to the nations.[32] The NT, though, often presents the people of God (the church), rather than ethnic Israel, in contrast to the nations. Many times NT authors are using ἔθνη merely to refer to those of non-Jewish ethnicity, or “Gentiles” (e.g., Mark 7:26; Acts 11:1); in numerous NT examples, though, ἔθνη specifies the identity of a qualitatively distinctive kind of people rather than an ethnically distinctive people. “The Gentiles” in many cases are those who are the characteristically unbelieving people of the world in contrast to the people of God. This NT usage of “the Gentiles/the nations” is quite consistent with how the OT speaks of “the nations.” For example, these statements sound quite similar to the OT warnings about following in the ways of “the nations”:

- “When you pray, do not heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles do.” (Matt 6:7)

- “You must no longer walk as the Gentiles do, in the futility of their minds.” (Eph 4:17)

- “The time that is past suffices for doing what the Gentiles want to do, living in sensuality, passions, drunkenness, orgies, drinking parties, and lawless idolatry.” (1 Pet 4:3)

Other NT writers, however, do not refer to the distinction between God’s people and “the Gentiles.” John, for example, presents distinctive terminology (“the world”) to refer to the contrast between God’s people and unbelievers. Scholars have recognized the key role of polarities, or dualisms, in John’s theology, and John establishes a strong polarity between the church and the world.[33] The Johannine worldview presents a “cosmic conflict between the world of light and the world of darkness” demonstrated primarily in the “struggle between God and his Messiah on the one hand and Satan on the other.”[34] Prominent in John’s writings is the idea that Satan is the ruler of this κόσμος, and he opposes Christ and believers (John 12:31; 14:30; 16:11; cf., 1 John 5:19). Ladd perhaps provides the most succinct summary of John’s concept of the world: “Man at enmity with God.”[35] In John’s writings, this conflict begins with Jesus’s conflict with the world and extends into a further conflict between the followers of Jesus and the world—enmity between believers and unbelievers.[36]

Distinctive Terminology in the Gospels & Acts

John’s writings provide a well-developed theology of “the world,” and he speaks about the world in concepts that parallel the way the Gospels and Acts speak of “the nations.” The Synoptics display a sharp contrast between God’s people and τὰ ἔθνη (“the Gentiles”), compared to John’s contrast between God’s people and the κόσμος. John’s key word in describing the world in opposition to the church is κόσμος. In general, scholars agree on three primary senses for κόσμος: (1) the created material world (John 17:5, 25), (2) humanity in general (John 1:29; 3:16–17), (3) sinful humanity in opposition to God and his people (John 14:27; 17:9). John uses κόσμος a total of 78 times in his Gospel. In comparison, the Synoptic writers use κόσμος only 15 times (8 in Matt; 3 in Mark; 4 in Luke-Acts)[37] and only in the general sense of the created universe (e.g., Matt 4:8; 16:26; 24:21; Mark 14:9; Luke 11:50; Acts 17:24) or the mass of humanity (e.g., Matt 18:7).

John’s Gospel, on the other hand, never uses the plural ἔθνη (it uses singular ἔθνος a total of 5 times), whereas the Synoptics and Acts use plural ἔθνη (“nations”) a total of 57 times (12 in Matt; 4 in Mark; 7 in Luke; and 34 in Acts).[38] Though the terminology is different, all of the Gospel writers agree in their assessment of the relationship between the world and believers, and they refer to “the nations” and “the world” in correlation with the same key themes. Table 1 (below) demonstrates that the Synoptics (with Acts) and John are using these two different terms in generally consistent ways and are conceptually parallel.

Table 1. κόσμος in John and ἔθνη in the Synoptic Gospels

| Description | Synoptics/Acts – ἔθνη | John – κόσμος |

| Object of Christ’s mission | Matt 4:15; 12:18,21; Luke 2:32; Mark 11:17; Acts 26:23 | 1:9; 3:17,19; 9:5; 12:46; 17:11 |

| Rejects Christ | Matt 20:19; Luke 18:32; Mark 10:33; Acts 4:25, 27 | 1:10; 7:7; 15:18, 24 |

| Rejects believers | Matt 24:9; Luke 21:24; Acts 14:2, 5; 21:11 | 15:18–19 |

| Distinct from God’s people | Matt 10:5,18 | 14:17,19,22; 17:6,9,16,25 |

| Distinct behavior as sinners | Matt 6:32; 20:25; Luke 12:30; 22:25; Acts 14:16 | 14:27; 16:8,20 |

| Object of mission of believers | Matt 24:14; 28:19; Luke 24:47; Mark 13:10; Acts 9:15; 10:45; 11:1, 18; 13:46–48; 14:27; 15:3, 7, 12, 14, 17, 19; 18:6; 21:19; 22:21; 26:17, 20; Acts 28:28 | 17:18–23 |

| Object of impending judgment | Matt 25:32; Luke 21:25 | 9:39; 12:31; 16:8,11 |

The Synoptics, therefore, use different terminology to speak of a similar dualism/polarity between God’s people and the unbelieving world to that of which John speaks.

Table 1 (above) shows that the Synoptics/Acts and John are speaking of quite similar concepts when they refer to the Gentiles (Synoptics/Acts) or the world (John) in contrast to the church. It is necessary, then, to ask why the Synoptics and Acts use different terminology than John to speak of this same basic distinction between God’s people and the unbelieving world. Matthew, for example, writing at an earlier date,[39] is writing with “the Jewish Christian church and the Jewish people in mind.”[40] In Matthew’s Gospel in particular, “Jewish issues are uppermost.”[41] Matthew, therefore, seems to be continuing the OT distinction between God’s people and “the nations” or “the Gentiles.” John, however, likely writing after the destruction of the temple,[42] no longer limits his focus to Jewish believers in contrast to the Gentiles; rather, John’s focus is now on the relationship between Jesus and the world and between the church and the world. By the time John is writing, the church is no longer centralized in Jerusalem with the Gentiles as outsiders; rather, the church is established throughout mostly Gentile geographical locations. It is no longer relevant to speak of God’s people in contrast to the Gentiles since the church is beginning to be more and more Gentile in makeup.[43] The church is spreading throughout the world, and John accommodates his language to this fact. It is difficult, therefore, to avoid seeing the conceptual parallels in the relationship between Israel and the nations in the OT and the church and the world in the NT.[44]

Parallel Concepts with the OT in the Gospels & Acts

The four primary themes identified in the OT concept of God’s people in contrast to the nations are prominent in the distinction between God’s people and “the Gentiles” in the Synoptics and Acts and between believers and the world in John’s Gospel.

God’s People as Distinct from the Gentiles/the World

The Synoptic Gospels present the “Gentiles” as a group of people set in distinctive contrast to God’s people. When Jesus commissions the twelve, he instructs them to “go nowhere among the Gentiles” but to go “rather to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt 10:5). When Jesus expands these instructions to encompass the future ministry of his disciples, he clearly warns that they should expect to be dragged before the Gentiles (ἔθνη) for judgment for Jesus’s sake (Matt 10:18). Because the people of God were primarily Israelites during the ministry of Jesus, Jesus still speaks of this future distinction between God’s people and the unbelievers of the world as a Jew/Gentile distinction.[45] Similarly, in Jesus’s teaching on church discipline, if the sinner is unresponsive to the correction given by the ἐκκλησία, the ἐκκλησία should treat the person as a “Gentile” (ἐθνικός) and a tax collector (Matt 18:17). The implication is that if the person is not an obedient member of the ἐκκλησία, he is a Gentile, a “person who has no place among the holy people of God.”[46]

In the Olivet Discourse, Jesus tells the disciples that they “will be hated by all nations [ἔθνη]” for the sake of Jesus’s name (Matt. 24:9). This instance certainly speaks of the nations as representative of unbelieving humanity in opposition to the people of God who are delivered up to tribulation. The distinction here cannot be a strict ethnic one between Jew and Gentile; it must be a qualitative distinction between the church and the unbelieving Gentiles (and Jews) among all nations since the church rather than Israel is now the entity through whom God is working to deliver the “gospel of the kingdom” to “the whole world as a testimony to all nations” (Matt 24:14).[47]

John presents this same distinctiveness between God’s people and the world. For example, the world is not able to receive the Spirit of truth “because it neither sees him nor knows him” (John 14:17). Jesus then says, “Yet a little while and the world will see me no more, but you will see me” (14:19). Jesus is “comparing the (eschatological) experience of the disciples to the world. The departure of Jesus changes his relationship to the world, but not to the disciples. . . . Once Jesus leaves, the world will no longer see him in the flesh, and they have never known him by the Spirit.”[48] Because the Jews were awaiting a Messiah who would reveal himself to the world,[49] Judas (not Iscariot) asks how Jesus can reveal himself to his disciples and not to the world (14:22). Those who love him keep his word and will have a home with Jesus and the Father (14:23–34). The Spirit has a distinctive ministry to believers that he does not have for the world.

This distinction between believers and the world is a prominent theme in Jesus’s prayer in John 17. The Father gave Jesus people “out of the world” (John 17:6; cf. 15:19). Jesus is praying specifically for these individuals and not for the world (17:9).[50] Jesus’s followers are not “of the world” just as Jesus is not “of the world.” Jesus is not asking the Father to take them out of the world but to protect them from the evil one (17:14–16). Jesus concludes the prayer distinguishing between the world, which does not know the Father, and believers, who know that the Father sent Jesus (17:25). Therefore, the Synoptics present the people of God in the church age in contrast to “the Gentiles,” whereas John presents the people of God in the church age in contrast to “the world.”

God’s Desire to Bless the Nations/the World

God desires to bring salvation to the nations/the world through Jesus and the church. In several instances, Matthew emphasizes Jesus’s mission to the nations. Matthew cites Jesus’s ministry in Capernaum as a fulfillment of Isaiah 9:1–2, in which “Galilee of the Gentiles [ἔθνη]” is a region which contains a “people dwelling in darkness” who “have seen a great light” (cf. Matt 4:15).[51] France highlights the theme of Gentile mission in Matthew: “By including ‘Galilee of the nations’ in his quotation Matthew gives a further hint of the direction in which his story will develop until the mission which will be launched from Galilee in 28:16 is explicitly targeted at ‘all nations’ (28:19).”[52] Later, Matthew cites Isaiah 42:1–3 in reference to Jesus as God’s Spirit-empowered Servant who will “proclaim justice to the Gentiles [ἔθνη]” (Matt. 12:18). It is in the name of this Servant that the Gentiles [ἔθνη] will hope (12:21). Similarly, in Luke 2, Simeon thanks God that his eyes have seen God’s salvation, “a light for revelation to the Gentiles [ἔθνη] and for glory to your people Israel” (Luke 2:30–32; cf. Isa 42:6; 49:6). Simeon’s statement affirms that the expectation of a Messiah for the nations is alive and well prior to the ministry of Jesus and the inception of the church. Finally, in Mark’s gospel, after Jesus cleanses the temple, Jesus quotes Isaiah 56:7, “My house shall be called a house of prayer for all the nations” (Mark 11:17).[53]

Since Jesus’s mission is ultimately to all nations, so he also commissions believers to witness to the nations. In the Olivet Discourse, Jesus says that “this gospel of the kingdom will be proclaimed throughout the whole world as a testimony to all nations [ἔθνη], and then the end will come” (Matt 24:14; cf. Mark 13:10). In the Great Commission, Jesus tells the disciples that they are to go and “make disciples of all nations [ἔθνη]” (Matt 28:19–20). In Luke’s version of the Great Commission, Jesus says that “repentance for the forgiveness of sins should be proclaimed in his name to all nations [ἔθνη]” (Luke 24:47). Therefore, as in the Old Testament, so also the NT writers emphasize the role of the Messiah and the people of God in ministering to all nations.[54] This blessing to “the nations” is a key theme in Acts, where ministry to the Gentiles receives prominence. Paul is “a chosen instrument” to “carry my name before the Gentiles and kings and the children of Israel” (Acts 9:15; cf. 22:21; 26:17). Though Paul’s custom was to go to the Jews first, he would then turn to the Gentiles (13:46–47; 18:6; 26:20). Paul’s mission to the Gentiles follows the pattern of the mission of Christ, who suffered and was raised that “he would proclaim light both to our people and to the Gentiles” (26:23). The Holy Spirit is poured out on the Gentiles (10:45), and the Gentiles receive salvation (11:1, 18; 13:48; 14:27; 15:3; 21:19; 28:28).

Parallel to Jesus’s ministry to the nations in the Synoptics is Jesus’s ministry to the world in John. Jesus is the true light, which gives light to everyone (John 1:9); Jesus frequently speaks of his mission in terms of “coming into the world” (John 1:9; cf. 3:19; 6:14; 9:5; 10:36; 11:27; 16:28; 17:18; 18:37). God sent his Son into the world “in order that the world might be saved through him” (3:17; cf. 3:16; 4:42; 12:47; 1 John 4:9, 14). Jesus is the bread of God who “gives life to the world” (John 6:33; cf. 6:51). Jesus says, “I have come into the world as light, so that whoever sees me sees him who sent me” (12:46; cf. 8:12; 11:9). Jesus is speaking to the world what he has heard from his Father (8:26; cf. 18:20), and he testifies to the truth (18:37). Similarly, as the Father sent Jesus into the world, so Jesus has also sent his followers into the world (17:18). Jesus declares that the mission of believers in the world is that people (in the world) “will believe in me through their word” (17:20) and “that the world may believe that you have sent me” (17:21).

John clearly presents the ministry of Jesus and the disciples as to the world, whereas the Synoptics and Acts consistently present the ministry of Jesus and the disciples as to the Gentiles. Table 2 (below) compares the similarities in key statements of the Synoptics and of John regarding the mission of Christ and believers to the nations/the world.

Being Distinct from the Gentiles/the World

The Gospels and Acts teach that God’s people must not emulate the sinful practices of the Gentiles/the World. The Synoptics present the idea that there is a certain stereotypical way of life, a certain mindset that “the Gentiles” engage in that is in opposition to the way in which God wants his people to live. Living like “the Gentiles” is in direct contradiction to living in a godly way. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus instructs his hearers not to be anxious about what they should eat, drink, or wear, “for the Gentiles [ἔθνη] seek after all these things” (Matt 6:32). In Luke’s parallel account, Jesus says that “all the nations [ἔθνη] of the world seek after these things” (Luke 12:30). Kingdom citizens should not greet only their brothers—even the Gentiles (ἐθνικός) do this (Matt 5:47). Also, when God’s people pray, they must not “heap up empty phrases as the Gentiles [ἐθνικός] do, for they think that they will be heard for their many words” (Matt 6:7). When Jesus is teaching the disciples about humility, he says that “the rulers of the Gentiles [ἔθνη] lord it over them. . . . It shall not be so among you” (Matt 20:25–26; Luke 22:25). Jesus, therefore, repeatedly urges his followers to Table 2: Mission to the Nations/the World

| Synoptics | John |

| “A light for revelation to the Gentiles and for glory to your people Israel.” (Luke 2:30–32) | “The true light, which gives light to everyone, was coming into the world.” (John 1:9) |

| “I will put my Spirit upon him, and he will proclaim justice to the Gentiles.” (Matt 12:18) | “God did not send his Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved through him.” (John 3:17) |

| “Galilee of the Gentiles—the people dwelling in darkness have seen a great light, . . . on them a light has dawned.” (Matt 4:15–16) | “I have come into the world as light, so that whoever sees me sees him who sent me.” (John 12:46) |

| “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations.” (Matt 18:19) | “As you sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world. . . that the world may believe that you have sent me.” (John 17:18–22) |

resist being like “the Gentiles.” Smillie comments, “Insofar as the

conventions reflect syllogistic Jewish logic—the unrighteous are those who do not know or do the Law of God, Gentiles do not know and thus cannot do the Law of God, therefore Gentiles are the unrighteous—Matthew is willing to use them, sparingly, to present stereotypical and characteristic behavior to be avoided by the new community.”[55] Additionally, in Acts, Paul tells the people at Lystra, “In past generations he allowed all the nations [ἔθνη] to walk in their own ways.” The Gentiles, therefore, exhibit certain behavioral characteristics that are distinct from how God’s people should behave.

Not only do the Gentiles live characteristically sinful lifestyles, but they clearly set themselves in opposition to Christ and his people. The Gentiles play a significant role in putting Jesus to death. Jesus foretells that priests and the scribes will “deliver him over to the Gentiles to be mocked and flogged and crucified” (Matt 20:18–19; cf. Luke 18:32). Mark adds that the Gentiles “will mock him and spit on him, and flog him, and kill him” (Mark 10:33). The Gentiles will also extend this hostility to believers as believers seek to minister to the Gentiles. As they go, believers will “be hated by all nations [ἔθνη]” because of Jesus’s name (Matt 24:9).

John’s Gospel highlights the sinful nature of this world in opposition to Christ and believers. John presents Satan as the ruler of this world. Jesus’s judgment on the world includes his exorcism of Satan from the world: “now will the ruler of this world be cast out” (John 12:31).[56] The ruler of this world has no claim on Christ (14:30) and will certainly be judged (16:11). Because the world follows the patterns of its ruler and it does not see or know the Father (14:17, 19), John speaks of the world as categorically sinful and opposed to Jesus’s ministry. The world gives a certain kind of peace that is inherently different from the kind of peace Jesus gives (14:27). Whereas the world speaks of peace merely in terms of “absence of conflict,”[57] Jesus provides internal peace in the midst of conflict (14:1ff.). When the Comforter comes, he will convict the world of sin because the world does not believe in Jesus (John 16:8–9).

This distinctive behavior of the world displays itself prominently in the world’s rejection of Jesus. Jesus “was in the world, . . . yet the world did not know him” (John 1:10). Indeed, the world hates Jesus because he testifies that its works are evil (7:7; cf. 15:18). The world hates both Jesus and the Father (15:23–24). Because the world hates Jesus and Jesus chose believers out of the world, the world also hates believers (15:18–19). When Jesus departs from the world, the disciples will weep and lament, but “the world will rejoice” (16:20). John’s Gospel, therefore, clearly presents the world as a mass of unbelievers who have a distinctively sinful lifestyle and who by nature oppose Jesus and his followers. The Synoptics and Acts similarly speak of living like “the Gentiles” as a distinctively sinful lifestyle, and the Gentiles work to oppose Christ and his followers.

Judgment on the Nations/the World

The theme of judgment on “the nations” is not prominent in the Synoptic Gospels; it is, nevertheless, present.[58] Though God desires to bring salvation to the nations through Jesus and his people, those Gentiles who reject Christ will be judged in the last days. Luke’s Olivet Discourse indicates that the nations on the earth will be distressed and perplexed because of the roaring of the sea and the waves that precedes the coming of the Son of Man (Luke 21:25). Then at the second coming, Jesus will sit on his throne, and all the nations will be gathered before him. Out of the nations, Jesus will separate the sheep from the goats (Matt 25:31–32). The focus of the majority of the judgment passages in the Synoptics, however, involves judgment on those who reject Christ and his kingdom, and these are not identified as “Gentiles.” This is likely due to the fact that by the time the Gospel accounts were written, the church included numerous Gentiles and was geographically spread across Gentile lands. Judgment on “the Gentiles” is only on those who are stereotypical Gentiles—those who reject faith in Christ.

In John’s Gospel, however, the world is destined for judgment. Jesus says, “For judgment I came into this world, that those who do not see may see, and those who see may become blind” (John 9:39). The judgment that is to come on the world comes through the death of Christ. This judgment presents the ultimate irony in that the ruler of this world executes judgment on Jesus, effecting the death of Jesus; but Satan’s judgment on Jesus is the ultimate means of Jesus’s judgment of the world and victory over the ruler of this world (John 12:31–32). When Jesus departs from the world, then the Comforter will convict the world concerning sin, righteousness, and judgment. Prominent here is that the Comforter’s conviction of the world is based on the judgment executed on the ruler of this world (16:8–11). Though believers will have tribulation in the world, Jesus assures them that he has overcome the world (16:33). In light of the “cosmic trial” motif, Jesus is both a witness and the judge who seeks to do the will of His Father (5:22–30; 9:39; 12:47–48). In a twist of Johannine irony, “it is not so much Jesus who is on trial as those to whom he has been sent, those who are acting as his judges.”[59] In the end, the world rejects Jesus, pronouncing their own condemnation in their condemnation of Jesus (3:18).

The Gentiles and the World in Paul’s Epistles

The NT epistles continue to distinguish between God’s people and the mass of unbelievers using the same terminological distinctions exemplified in the OT and in the Gospels and Acts. Paul employs both sets of terms in different places, and Peter consistently refers to “the Gentiles,” whereas James and John refer to “the world.”

Paul’s use of “the Gentiles” generally parallels the way the Synoptics refer to the Gentiles. Paul uses ἔθνος 54 times, 52 of which are the plural ἔθνη, often merely referring to the Gentiles as a non-Jewish ethnicity (e.g., Rom 1:13; 3:29; 11:11). Paul uses two key terms to refer to the world (αἰών and κόσμος). Paul uses αἰών primarily to refer to the arena over which Satan exercises influence. The basic sense of αἰών refers to a long period of time (Eph 1:21; Col 1:26), but Paul distinctively describes this present αἰών as categorically evil (Gal 1:4; Eph 2:2; 2 Tim. 4:10).[60] Paul uses κόσμος, on the other hand, to refer to either the created world in a geographical sense (e.g., Rom 1:8, 20; Eph 1:4) or to the mass of humanity in the world (Rom 3:19).[61] Related to the latter sense, κόσμος can also carry a pejorative overtone in reference to unbelieving humanity and its thought/behavior patterns (e.g., 1 Cor 1:21; 3:19). Paul’s usage of “the Gentiles” and “the world” fit in the same categories as “the nations” and “the world” do in the OT and in the Gospels and Acts.

Distinct from the Gentiles/the World

Paul speaks of the Gentiles as distinct from the people of God in the sense that they are unbelievers who need the gospel and that they are known to be stereotypically sinful in their behavior (see the two subsequent sections below). The world did not know God through wisdom; God saves those who believe (1 Cor 1:20). The spirit of the world is contrasted with the Spirit of God (1 Cor 2:12). Paul also differentiates between a godly grief and a worldly grief (2 Cor 7:10). Paul speaks of the life of a believer in contrast to the former life “as Gentiles” (Eph 4:17; 1 Th. 4:5) and in contrast to “this age” (αἰών; Rom 12:2) and “the world” (κόσμος; 1 Cor 1:20–21; 6:2). In Ephesians 2:2, Paul refers to a pre-conversion lifestyle characterized by “the age of this world” (τὸν αἰῶνα τοῦ κόσμου τούτου). Lincoln argues that this usage of both key terms in Ephesians 2:2 may be “a way of talking about both spatial and temporal aspects of fallen human existence.”[62]

Mission to the Gentiles and the World

Paul declares himself to be “an apostle to the Gentiles” (Rom 11:13), and numerous Pauline passages speak of Paul’s desire to bring the gospel to the Gentiles (Rom 1:5, 13; 15:9–12, 16–18, 27; Gal 1:16; 2:2; 3:8, 14; Eph 3:6, 8; Col 1:27; 1 Tim 2:7; 2 Tim 4:17).[63] God is the God of the Gentiles also (Rom 3:29), and Abraham is the father of many nations (Rom 4:17–18). The OT “preached the gospel beforehand to Abraham” when God tells Abraham that all nations would be blessed in him (Gal 3:8). Therefore, Christ became a curse for us “so that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles” (Gal 3:13–14). Similarly, Paul teaches that Christ came to bring salvation to the world. Jesus “came into the world to save sinners” (1 Tim 1:15). Christ’s work on the cross includes reconciling the world to himself (2 Cor 5:19), and he encourages the Philippians to shine as lights in the world (Phil 2:15).

Being Distinct from the Gentiles/the World

Paul views the Gentiles as the paradigm for lost humanity (Rom 2:14, 24). There is a distinct behavior associated with the Gentiles (1 Cor. 5:1). And in their former lives, the Corinthians were “pagans” (ἔθνη in 1 Cor 12:2), and such Gentiles had been putting Paul’s life at risk (2 Cor 11:26). Paul asserts, “We ourselves are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners” (Gal 2:15). He instructs the Ephesians not to “walk as the Gentiles do” (Eph 4:17). The Thessalonians must not live “in the passion of lust like the Gentiles who do not know God” (1 Thess 4:5). Paul presents the Gentiles as those who are unconverted and live characteristically evil lifestyles.

As the church must not live as the Gentiles do, so Paul warns against living like the world. The unbelievers in this world are characteristically “sexually immoral . . . greedy and swindlers, or idolaters” (1 Cor 5:10). Before conversion, people are “following the course of this world,” which is equivalent to “following the prince of the power of the air” (Eph 2:2). Satan, therefore, is the driving force behind the world and its ways. Believers, however, have died to “the elemental spirits of the world (Col 2:8, 20). Paul’s most extensive discussion of the world is in the early chapters of 1 Corinthians. The world does not know God through its wisdom (1 Cor 1:21), and its wisdom is folly with God (3:19). Paul here is promoting a “response to the world which . . . may be described as sectarian. This world, according to Paul in his statements on κόσμος, is a corrupt and hostile place.”[64] The problem in Corinth is that “the church is failing to maintain its distinctiveness within its wider social and cultural environment.”[65] Paul urges believers that they must live distinctly from the world.

Judgment on the Gentiles/the World

Paul never speaks of judgment on “the nations.” As with the Gospels, there is a concerted effort to avoid expressing that Gentiles are under God’s judgment, since many Gentiles are part of the church. Paul does speak of judgment on the “world.” For Paul, the judgment to come upon the world is certain (Rom 3:6; 19), and the sinful people of the world will be judged (1 Cor 6:2; 11:32).

The Gentiles and the World in the General Epistles

The General Epistles continue using the same distinctions used by the Gospel writers and Paul, but each author tends to use either “Gentiles” or “world” to speak of the contrast between God’s people and unbelievers. Peter prominently uses “Gentiles” according to the pattern set by the Synoptics and Paul, whereas James and John both refer solely to the church’s distinction from the “world.”[66]

James and the World

James presents one of the key statements in the NT regarding the world (Jas 4:4), but he never uses ἔθνος. It could even be argued that “enmity with the world” represents the “thematic center” for James’s theology, demonstrated in James’s “ethical and religious dualism.”[67]Darian Lockett argues that “James charts the universe via two competing world views, or systems of value. . . . Not only are these systems of measure set in opposition, but ‘the world’ is expressly marked off as contagious territory—polluting ground (Jas 1:27).”[68]James consistently refers to what is worldly or earthly to “refer to the world as a counter measure of order over against the order of God.”[69] Remaining unstained from the world requires believers to “maintain a particular boundary between themselves and the influences of ‘the world.’”[70] The world is “the agent of pollution” that “transmits a counter form of ‘religion’” that contaminates believers.[71]These themes are consistent with the OT idea of the nations as “contagious territory” and representing the realm of humanity opposed to God.

As John and Paul both identify Satan as the ruler of this world, James also speaks of the ongoing warfare believers engage in with the devil (Jas 4:7). James contrasts wisdom that comes from above (from God) with wisdom that is “earthly, unspiritual, demonic” (Jas 3:15). The demonic nature of this wisdom indicates that it is “instigated by demons and the unwholesome spiritual world.”[72] The reference to “world” (κόσμος) in 4:4 (as in 1:27) cannot refer to the mass of humanity in general or to the evil people of the world but rather to the way of life in which unbelievers characteristically engage. Believers must hold back from friendship with the world, which represents “the ethos of life in opposition to, or disregard of, God and his kingdom.”[73] In keeping with the recurring theme in the letter, the reference to friendship of the world relates to behaviors and lifestyle. James is urging the people to adopt a lifestyle distinct from the world.

Peter and the Gentiles

Peter wants believers to honor God through their fiery trials, and his exhortation for overcoming in the face of this enmity is grounded in God’s intention for them as specified in their identity as believers. First Peter 2:9 serves as “the basis for the following exhortation concerning the behavior of God’s family in society.”[74] Peter tells them that they are “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession” (2:9), language that certainly alludes to Exodus 19:5–6.[75] Peter identifies the purpose of the church in this hostile, evil world as parallel to God’s purpose for Israel among the hostile, evil Gentiles.[76] Believers are to serve as witnesses to the unbelievers (the Gentiles), while they are to maintain holy lives before God. Peter’s ensuing exhortations address (1) living distinctively from the Gentiles (a holy nation) and (2) showing the unbelievers through words and actions how they may know God (royal priesthood). These two elements are the key principles in 2:11–12: “Abstain from the passions of the flesh. . . . Keep your conduct among the Gentiles honorable, so that . . . they may see your good deeds and glorify God.” The remainder of the letter elaborates on these points.

Peter uses “Gentiles” to refer to a stereotypical, unconverted, sinful way of life. Before their conversion, believers had already spent enough time doing what “the Gentiles” do (1 Pet 4:3). This usage is similar to Paul’s instruction to “no longer walk as the Gentiles do” (Eph 4:17). Whereas Paul urges believers not to be conformed to “this world/age” (Rom 12:2), Peter urges believers not to be “conformed to the passions of your former ignorance” (1 Pet 1:14). Also, Peter refers to “the Gentiles” (τὰ ἔθνη) in the same way in which John sometimes refers to the “world” (κόσμος). Peter’s instructions to maintain honorable conduct among the Gentiles (1 Pet 2:12) and to avoid doing “what the Gentiles want to do” (1 Pet 4:3) are parallel with Jesus’s statements about being “in the world” but not “of the world” (John 17:11–18). Furthermore, God’s intention is to bring salvation to the Gentiles. When believers witness in this way to Gentiles, if the Gentiles believe, they will “glorify God on the day of visitation” (1 Pet 2:12). If they refuse to believe, however, these Gentiles “will give account to him who is ready to judge the living and the dead” (1 Pet 4:5; cf. 4:17–18).

John and the World

As noted in the discussion of John’s Gospel above, John’s use of “world” is distinctive in the NT. John prominently uses “world” in his epistles as well, and he avoids referring to the “nations” or “Gentiles” (he refers to “Gentiles” only in 3 John 7). First John 2:15–17 pronounces the letter’s key statement on the world: “Do not love the world or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. . . . The world is passing away along with its desires.”[77] The things that are “of the world” are “not of the Father” because they are under the power of the evil one (1 John 5:19). Those who are not among believers are “from the world” (1 John 4:5), and believers should not be surprised that the world hates them (1 John 3:13). John’s epistles, therefore, fully display the key themes from the OT and the NT surrounding the relationship between the people of God and the world. John identifies the world as a group distinct from God’s people (1 John 3:1; 4:5) and who are characteristically evil (1 John 3:13; 4:4; 2 John 7). God, however, has sent Jesus to save the world (1 John 2:2; 4:9, 14), but those who resist him will be overcome (1 John 5:4, 5).

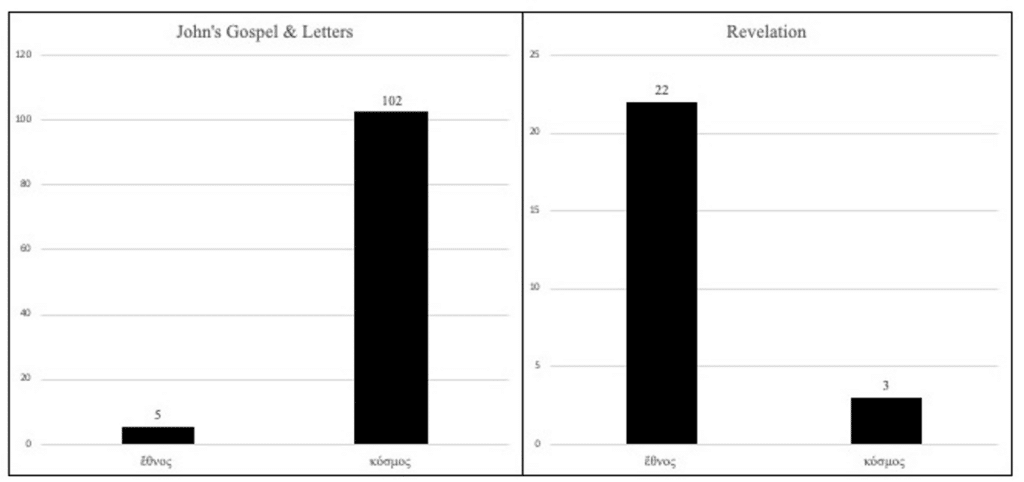

The Gentiles and the World in Revelation

A fascinating development in a study of the NT use of ἔθνος and κόσμος is the frequency of John’s use of ἔθνος in Revelation (22x) compared to John’s Gospel and letters (5x). It appears that John is replacing his favored term κόσμος (which is used 102 times in John’s Gospel and Letters but only 3 times in Revelation) with ἔθνος. Two of the three uses of κόσμοςin Revelation refer to the basic sense of the “world” as the created universe (“the foundation of the world” in 13:8 and 17:8). The third use of κόσμος, though, is quite significant and is more in line with John’s usage elsewhere: “The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ, and he shall reign forever and ever” (11:15). Figure 1 displays the contrast in John’s usage of κόσμος and ἔθνος in John’s writings.

Figure 1: John’s Use of κόσμος and ἔθνος

The question of why John uses ἔθνος instead of κόσμος throughout Revelation is certainly worthy of discussion. Part of the reason is likely the overwhelming number of allusions to the OT in Revelation. Since the OT consistently uses ἔθνος instead of κόσμος to refer to the people who are in opposition to God, it is natural to expect John to continue with the OT usage. G. K. Beale points out John’s tendency in Revelation “to apply to the world what in the Old Testament was limited in reference to Israel or other entities.”[78] Additionally, Revelation, as the final installment of biblical revelation, is weaving together all the key threads of prior revelation. This prior revelation includes God’s promise to bless all nations through Abraham, as well as the long-standing enmity between the people of God and the nations—and between the kings of the earth and his Anointed one (Ps. 2). John, therefore, may be using ἔθνος to highlight how Revelation demonstrates how these OT themes come to their final climax. Upon review of John’s use of ἔθνος in Revelation, the four key themes prominent in the OT and in the rest of the NT take prominence in Revelation as well.

“The Nations” as Distinct from the People of God

The people of God who are worshiping before the throne have come out “from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages” (7:9; cf. 5:9). The nations in Revelation are frequently seen as an entirely separate entity from God’s people. The points below demonstrate numerous ways in which “the nations” are a group that is distinct from the people of God.

Blessing to the Nations

God desires to bless the nations, and this promise of blessing is finally fulfilled in Revelation. Bauckham notes that “The question of the conversion of the nations—not only whether it will take place but also how it will take place—is at the centre of the prophetic message of Revelation.”[79] Representatives from every nation are ransomed by the Lamb (5:9) and stand before him worshiping (7:9). An angel later commands the nations to “fear God and give him glory” (14:7). In the song of Moses and of the Lamb, the multitude declares God to be the “King of the nations” (15:3) and that “all nations will come and worship” him (15:4). In this way, “John has interpreted the song of Moses in line with the most universalistic strain in Old Testament hope: the expectation that all the nations will come to acknowledge the God of Israel and worship him.”[80] Indeed, the church plays a crucial role in the salvation of the nations: “the church was not redeemed from all nations merely for its own sake, but to witness to all nations. . . . God’s kingdom will come, not simply by the deliverance of the church and the judgment of the nations, but primarily by the repentance of the nations as a result of the church’s witness.”[81] In the heavenly city, the Lamb is the lamp that gives the light of the glory of God, and it is by this light that the nations will walk (21:24).[82] Then on either side of the river, the tree of life stands, and “the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations” (22:2).

The Nations as Distinctively Sinful in Their Opposition to the People of God

The nations are distinctively sinful and opposed to God and his people. Revelation consistently aligns the nations with the “powers of evil” (14:8; 18:3, 23; 20:3).[83] Though some are called out from the nations to be God’s people, Revelation also speaks of the nations as categorically evil and under the influence of the beast. It is the beast that exercises authority over every tribe, people, tongue, and nation (14:6). The beast rules Babylon the great, who made “all nations drink the wine of the passion of her sexual immorality” (14:8; 18:3). All nations were deceived by the sorcery of the great harlot, Babylon (18:23). The ultimate source of this deceit is the dragon, who is bound and thrown into a pit “so that he might not deceive the nations any longer, until the thousand years were ended” (20:3). After the thousand years, Satan will be released and “will come out to deceive the nations that are at the four corners of the earth” to gather them for battle against the saints (20:7–8).

Judgment on the Nations

Revelation displays God’s final judgment on the nations. At the seventh trumpet the twenty-four elders fall on their faces and worship God, saying, “The nations raged, but your wrath came” (Rev 11:18), a certain allusion to Psalm 2 and to the wicked opposition to the divine redemption plan accomplished through Messiah.[84] As in Psalm 2, this wicked opposition to the Messiah results in divine wrath. The child who is born from the woman is the “one who is to rule all the nations with a rod of iron” (12:5). At the seventh bowl judgment, “the great city was split into three parts, and the cities of the nations fell, and God remembered Babylon the great, to make her drain the cup of the wine of the fury of his wrath” (16:19). When the King of kings returns on his white horse, out of his mouth proceeds a sharp sword “with which to strike down the nations” (19:15).[85]

Summary and Implications

The OT presentation of the people of God in their relationship to the surrounding nations provides the conceptual foundation for the church’s relationship to the world. Four key themes become evident in the OT describing Israel’s relationship to the other nations. (1) The nation of Israel represents the people of God in the OT, and they are distinct from the pagan nations who do not know Yahweh. (2) God’s promise to Abraham, though, is that through his descendants he will bless the nations. When God constitutes Israel as a nation, he declares their purpose to be a kingdom of priests, representing him to the surrounding peoples. (3) At the same time, they must remain distinct from “the nations” in their worship and lifestyle. (4) The customs of the nations are repulsive to Yahweh, and they will suffer the impending judgment unless they turn to him. Much of the remainder of the OT demonstrates how Israel failed to accomplish her mission. The NT presents the same contrast between the church and the world that the OT presents between Israel and the nations. Some NT writers refer to “the Gentiles” or “the nations” in contrast to the church, whereas others refer to the world in contrast to the church. The NT manifests the same key themes as the OT. The church is fundamentally distinct from the world. God intends for the church to witness to the nations/the world, while remaining distinct from the world and a “Gentile” lifestyle. In the final judgment, the world/the nations will be judged for their rejection of God.

Because the OT provides the conceptual foundation for the distinction between the church and the world, the principles regarding this distinctiveness found in the OT provide continuing relevance for the church’s distinctiveness from the world. Therefore, key areas of OT teaching on the holiness of God’s people and their distinctiveness from the nations continue to be relevant and necessary for NT believers. Because the NT warns so seriously against conformity to the world and because of how terrible the judgment on OT Israel was for its conformity to the nations, churches today must sincerely examine themselves to determine whether they are being seduced by “the evil enchantment of worldliness.”[86] In our post-Christian culture, Christians are tempted to compromise biblical truth to accommodate to the ungodly philosophy of the culture. The well-intentioned desire to transform the culture for Christ can create the impulse to be well-thought of by the culture in order to gain a hearing. Holding fast to unpopular “antiquated” views of complementarianism or anti-LGBTQ ideology creates a barrier between the Christian and the culture. The temptation then is either to render such unbiblical ideologies as unimportant or to adjust one’s position to make feminism and LGBTQ ideology compatible with Scripture. Christ, however, did not come to bring union between belief and unbelief. He came with a sword to divide them (Matt 10:34–36).

Another area of compromise with the world is in the philosophy of ministry of local churches. Even in churches that hold to orthodox doctrine and are not rejecting the Bible outright, the temptation to conform to the world is difficult to resist. As Israel looked to the nations to “enhance” its worship methods, many churches look to the unbelieving world to inform and enhance their worship services. The mindset for so many American seeker and consumer-centered churches is to “meet unchurched visitors where they are” and to “match your music to the kind of people God wants your church to reach.”[87] This mindset acknowledges the church’s willingness to look to the unbelievers of the world to determine the style of music the church should use. In an effort to be relevant and get more attendees in order to expand the kingdom, churches are tempted to ignore biblical precedent and principles, designing their ministry to look appealing or relevant or interesting to the masses. To accomplish this, churches shorten sermons, devote less time to pastoral prayer, incorporate dramas, and ensure that the “worship team” performs well for the people. Such churches may be able to entertain people and create an emotional experience; this is not the same thing as worshiping the holy God. In discussing the church’s tendency to try to accommodate all of the varied preferences of a demographic and “to reach them where they are at,” Brett McCracken wisely comments, “A better approach is to call the congregation in its diversity, to meet Christ where he is, even if it means asking people to redirect or abandon their various self-defined paths.”[88] McCracken then argues that Christians will lose interest in churches “whose weakened position in a secular age leads them to seek survival by assuming they must adjust to the restless whims and new spiritual paths of the ‘marketplace.’ It’s an unsustainable approach for churches, because it’s also a self-defeating path for churchgoers.”[89] Churches are not relevant when they provide unbelievers the same style of empty entertainment that they get the rest of the week. Churches will find that they are most relevant in a post-Christian culture when they are truly offering an alternative to the barren, self-exalting, Christ-rejecting, Satan-serving world that actively seeks the destruction of God’s kingdom.

[1] Jonathan M. Cheek, PhD, is an independent scholar living in Taylors, SC.

[2] Unless otherwise noted, this paper is referring to the concept of the “world” in terms of the evil people of the world or the evil system of the world rather than the world in a cosmological sense or in the sense of “all humanity.”

[3] Translations of Scripture are from the ESV unless otherwise noted.

[4] Most theological dictionaries and major works on New Testament theology devote some meaningful discussion to the topic. For example, see Donald Guthrie’s lengthy section on “the world” in New Testament Theology (Downers Grove: IVP, 1981), 121–50; and T. Renz, “World,” in NDBT, ed. T. D. Alexander, B. S. Rosner, D. A. Carson, and G. Goldsworthy (Downers Grove: IVP, 2000), 853–55.

[5] For example, see James Davidson Hunter, Evangelicalism: The Coming Generation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 63; David F. Wells, God in the Wasteland: The Reality of Truth in a World of Fading Dreams (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 29; No Place for Truth: Or Whatever Happened to Evangelical Theology? (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993), 11–12; Robert H. Gundry, Jesus the Word According to John the Sectarian: A Paleofundamentalist Manifesto for Contemporary Evangelicalism, Especially Its Elites, in North America (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 73–78; John MacArthur, Ashamed of the Gospel: When the Church Becomes Like the World, 3rd ed. (Wheaton: Crossway, 2010), 31; C. J. Mahaney, “Is This Verse in Your Bible?” in Worldliness: Resisting the Seduction of a Fallen World (Wheaton: Crossway, 2008), 22; Russell Moore, Onward: Engaging the Culture without Losing the Gospel (Nashville: B&H, 2015),1–10; Rod Dreher, The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation (New York: Sentinel, 2018), 12.

[6] See Wells, God in the Wasteland (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), 37.

[7] Most Bible/theological dictionaries handle the topic this way. See, for example, T. V. G. Tasker, “World,” in NBD, ed. I. Howard Marshall, et al., (Downers Grove: IVP, 1996), 1249–50; J. Painter, “World, Cosmology,” in DPL, ed. G. F. Hawthorne, R. P. Martin, and D. G. Reid (Downers Grove: IVP, 1993), 979–82;Carl Bridges, Jr, “World,” in EDBT, ed. W. A. Elwell (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996), 837.

[8] Renz, 853–55; Bruce K. Waltke, An Old Testament Theology (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2007), 281; Randy Leedy, Love Not the World: Winning the War Against Worldliness (Greenville, SC: BJU Press, 2012), 13–33; William Edgar, Created & Creating: A Biblical Theology of Culture (Grand Rapids: IVP Academic, 2017), 100. Of these, Leedy is the only author who writes more than a paragraph on this topic.

[9] Renz, 854; and Leedy, 13–33.

[10] Studies on “the nations” or “Gentiles” in Bible/theological dictionaries never develop a discussion of “the world” in the NT. For example, see Andreas Köstenberger, “Nations,” in NDBT, 676–78; K. R. Iverson, “Gentiles,” in Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels, ed. J. B. Green, J. K. Brown, and N. Perrin (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2013), 302–9; and Michael F. Bird, Jesus and the Origins of the Gentile Mission, LNTS (London: T&T Clark, 2006).

[11] See T. D. Alexander, From Paradise to the Promised Land: An Introduction to the Pentateuch, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2002), 101–113; and James Hamilton, “The Skull Crushing Seed of the Woman: Inner-Biblical Interpretation of Genesis 3:15,” SBJT 10, No. 2 (2006): 30–34.

[12] See Alexander, “Messianic Ideology in the Book of Genesis,” in The Lord’s Anointed: Interpretation of Old Testament Messianic Texts, ed. P. E. Satterthwaite, R. S. Hess, and G. J. Wenham (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1995), 19–39.

[13] גֹּוי, HALOT.

[14] The ESV uses the plural terms “nations” 452 times and “peoples” 226 times in the OT. It generally translates גֹּוי as “nation(s)” and עַם as “people(s).”

[15] Exodus, AOTC (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2017), 369.

[16] Eckhard J. Schnabel notes, though, that “when pagans find salvation, they join Israel (cf. Naaman), and when pagan nations find salvation, they will come to Zion (cf. Isa 40–66).” “Israel, the People of God, and the Nations,” JETS 45, No. 1 (March 2002): 36.

[17] W. Ross Blackburn, The God Who Makes Himself Known: The Missionary Heart of the Book of Exodus, NSBT (Downers Grove: IVP, 2012), 87.

[18] The Hebrew word translated “treasured possession” is סְגֻלָּה and is used eight times in the Old Testament. Six of the uses refer to Israel as Yahweh’s treasured possession (Exod 19:5; Deut 7:6; 14:2; 26:18; Ps 135:4; Mal 3:17). Victor P. Hamilton points out that the significance of this concept is that “Israel has a special relationship with the Lord that no other nation can claim or experience. . . . Israel alone is Yahweh’s sĕgullâ.” Exodus: An Exegetical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2011), 303.

[19] John A. Davies identifies five different interpretations of the meaning of this priestly ministry: “service to the nations, mediation of blessing or redemption to the nations, intercession for the nations, teaching the will of God to the nations, or a liturgical mission to the nations.” A Royal Priesthood: Literary and Intertextual Perspectives on an Image of Israel in Exodus 19:6, JSOT Supplement Series (London: T&T Clark, 2004), 95. Davies argues that the correct understanding of “kingdom of priests” is ontological and does not refer to Israel’s relationship to other nations. Priests are those who “draw near to Yhwh” (98). Though Davies’ understanding of the ontological nature of priesthood may be accurate, there is no reason to limit the interpretation to merely the ontological definition of priesthood. When Peter alludes to Exodus 19:5–6 to describe the church as “a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession,” he explicitly states the functional purpose for these descriptive phrases: “that you may proclaim the excellencies of him” (1 Pet. 2:10) and to “keep your conduct among the Gentiles [ἔθνη] honorable” so that they might “glorify God on the day of visitation” (2:12). If the Abrahamic Covenant speaks of Israel as a blessing to the nations, it is reasonable to expect the Mosaic Covenant to also speak of Israel’s role among the nations. Paul R. Williamson correctly observes, “The whole nation has thus inherited the responsibility formerly conferred upon Abraham—that of mediating God’s blessing to the nations of the earth.” Sealed with an Oath: Covenant in God’s Unfolding Purpose, NSBT (Downers Grove: IVP, 2007), 97.

[20] John I. Durham, Exodus, WBC (Waco, TX: Word, 1987), 263.

[21] The use of גּוֹי instead of עַם for “nation” may allude to God’s promise to make Abraham a great nation (גּוֹי, Gen 12:2). Blackburn argues that the use of גּוֹי generally refers to “an established political entity,” thus relating “Israel to the other nations of the earth by placing her in a similar category” (92–93).

[22] For example, Peter J. Gentry and Stephen J. Wellum argue that both statements taken together are “another way of saying, ‘God’s personal treasure.’” They explain that “both statements are saying the same thing, but each does it in a different way and looks at the topic from a different perspective.” Kingdom through Covenant: A Biblical-Theological Understanding of the Covenants (Wheaton: Crossway, 2012), (p. 316).

[23] The Promise-Plan of God: A Biblical Theology of the Old and New Testaments (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 76. See also Durham, 95.

[24] Forms of the word “holy” (קדשׁ, קֹדֶשׁ, קָדוֹשׁ) occur only one time in Genesis, but from this point forward, the word becomes prominent throughout the Old Testament with a particular emphasis in the Pentateuch. These three words occur 334 times in Exodus through Deuteronomy—44% of the 754 total occurrences in the Old Testament.

[25] Jackie A. Naudé, “קָדַשׁ,” in NIDOTTE, ed. Willem VanGemeren (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1997), 3:879.

[26] For this sense, see also Durham, 263; D. G. Peterson, “Holiness,” in NDBT, 550; Alexander, From Paradise to the Promised Land: 208–213; and Blackburn, 95. Peter J. Gentry is a notable exception to this. He argues that the “basic meaning of the word [קדשׁ] is ‘consecrated’ or ‘devoted,’” rather than that of separateness or moral purity. “The Meaning of ‘Holy’ in the Old Testament,” BibSac 170 (2013): 417. It is difficult, though, to comprehend in what sense God himself is “consecrated” or “devoted,” particularly in statements which command people to be holy as Yahweh is holy (Lev 11:44–45). Gentry acknowledges that moral purity is a result of one’s consecration to God, but he does not include the necessary element of separation from a sinful lifestyle. Gentry’s attempt to explain how God is “consecrated” or “devoted” in Isaiah 6:3 seems to be quite forced: “‘Holy’ means that He is completely devoted and in this particular context, devoted to his justice and righteousness, which characterizes His instruction of the people of Israel in the covenant, showing them not only what it means to be devoted to Him but also what it means to trust each other in a genuinely human way, in short, social justice” (413).

[27] “Nations,” in NDBT, 677.

[28] “Nations,” in NDBT, 677.

[29] In spite of this emphasis on the fact of the future salvation of the nations, Schnabel argues that the OT indicates that OT authors did not understand their role as one of outreach to the nations. Though one might speak of God reaching out to the nations, there is “no exegetical evidence that allows us to speak of examples of an outreach of the people of God” (39).

[30] Daniel I. Block, The Book of Ezekiel: Chapters 1–24, NICOT (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 201.

[31] The Synoptics use the plural ἔθνη 23 times. Matthew uses the plural ἔθνη 12 times, Mark 4 times, and Luke 7 times. Luke uses plural ἔθνη 32 times in Acts; Paul uses ἔθνη 52 times in his letters, and Peter uses ἔθνη two times. Matthew uses ἐθνικός three times, and John uses ἐθνικός once (in 3 John).

[32] The singular ἔθνος always refers to a “nation.” The plural ἔθνη may refer to “nations” or “Gentiles,” depending on the context, though the English terms overlap. In this paper, I have chosen to use the more appropriate term for each context in the NT.

[33] Not to be confused with Gnostic dualism, Andreas J. Köstenberger defines this type of dualism as “a way of looking at the world in terms of polar opposites” (A Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, BTNT [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009], 277). For helpful studies of Johannine dualism, see G. E. Ladd, A Theology of the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1974), 223–36; Judith Lieu, The Theology of the Johannine Epistles, NTT (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1991), 80–87; and Richard Bauckham, Gospel of Glory: Major Themes in Johannine Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2015), 109–29.

[34] Köstenberger, A Theology of John’s Gospel and Letters, 281.

[35] Ladd, Theology of the New Testament, 226.

[36] Bauckham defines this enmity as an “ethical dualism,” in which “two categories of humans, the righteous and the wicked, are contrasted” and a “soteriological dualism” in which “humanity is divided into two categories by people’s acceptance or rejection of a savior” (p. 120). He argues that these concepts develop as the enmity toward Jesus develops John’s Gospel. In the later chapters of John’s Gospel, “Jesus’s disciples, who are ‘not from the world’ and are ‘chosen from the world,’ become, along with Jesus, one of the two components of a dualistic contrast between them and the world” (Gospel of Glory, 128).

[37] The term κόσμος occurs 102 times combined in John’s Gospel and Letters, demonstrating the importance of κόσμος in John’s theology. The only nouns used more frequently in John’s writings are Ἰησοῦς (258x), πατήρ (154x), and θεός (150x).

[38] It is interesting that Matthew uses the term ἐθνικός three times (5:47; 6:7; 18:17). This word is quite similar in meaning to τὰ ἔθνη and refers to non-Jewish people with the connotation that they are ungodly.

[39] Numerous factors are involved in determining the date of the Gospels of both Matthew and John. The author agrees with the conclusion of D. A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo, which asserts the likelihood that Matthew’s Gospel was written prior to AD 70. An Introduction to the New Testament, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005), 152–56. Textual and historical evidence supports the idea that John’s Gospel was almost certainly later than AD 70, possibly around AD 80–85 (264–67).