I understand how difficult it can be for modern Christians to accept the fact that music embodies theology. Several hundred years of post-Enlightenment rationalism has influenced us to see music as amoral, without inherent meaning, and merely neutral “packaging” for lyrics.

However, this is not how Christians in the past have viewed music and its role in life and worship. In fact, this is not how anyone viewed music prior to the Enlightenment. And it is certainly not how Scripture views it.

My goal in this article is to introduce a biblical understanding of how music (all art, actually) embodies ideas and therefore must be evaluated as to its fittingness for carrying particular lyrical content or use in certain circumstances—especially Christian worship. Next week, I will specifically address how two prominent theologies of worship have cultivated two very different kinds of worship music.

What Accords with Sound Doctrine

A first important step to recovering a biblical understanding of art and music is to remind ourselves of what the Bible teaches about the necessary connection between our theology and our behavior. Paul says in Titus 2:1,

But as for you, teach what accords with sound doctrine.

What is Paul talking about here when he refers to “what accords with sound doctrine”? Is he talking about other intellectual truths that accord with doctrine? No, he tells us what kinds of things accord with sound doctrine in the following verses:

- sobriety

- dignity

- self-control

- soundness in faith

- soundness in love

- steadfastness

- reverence

- kindness

- purity

- industriousness

- integrity

In other words, “what accords with sound doctrine” involves qualities of character that manifest themselves in life behavior.

“What accords with sound doctrine” involves qualities of character that manifest themselves in life behavior.

And notice that while some of what Paul lists in these verses involves specific action (not being slaves to wine, wives submitting to husbands, etc.), most of what he discusses here involve inward qualities (dignity, reverence, etc.) that in many ways are difficult to precisely define or articulate. Words alone are often inadequate to describe these sorts of character qualities.

Let’s take reverence, for example. What is it? Clearly there must be an objective reality called “reverence,” but how would you describe it? It’s difficult, right?

But the difficulty in describing a character quality does not render it subjective. God commands us to be characterized by reverence, dignity, and self-control—these are what “accord with sound doctrine.” So we have a responsibility to discern what these qualities are like and cultivate them in our lives.

We must also recognize that these are non-verbal. We demonstrate these qualities (or lack thereof) through our behavior, through how we carry ourselves, through body language and vocal inflection. These are means of communicating inward qualities that extend beyond just what we say. If you doubt this, consider the next time your child speaks to you disrespectfully. What was disrespectful—what they said (sometimes, but not always) or how they said it?

How we speak matters just as much as what we say, because the way we communicate expresses non-verbal qualities.

In other words, the sorts of qualities Paul mentions in passages like Titus 2:1 are non-verbal embodiments of biblical theology.

Non-verbal Embodiment in Scripture

But as I mentioned above, the challenge with qualities like this is that words alone are often inadequate to precisely define them. So does this mean that Scripture is insufficient to communicate precisely “what accords with sound doctrine”?

Hardly, because we must remember that Scripture is more than abstract words. Of course Scripture is filled with words, but whenever you choose one word over another, whenever you put words into sentences and paragraphs, whenever you employ literary genre and artistic imagery, you are already embodying ideas.

Here’s one example. Let’s say I want to describe the age of a senior adult in my church. Which of the words below would he prefer I choose?

- ancient

- elderly

- frail

- rickety

- seasoned

Each of these words is technically true—they have the basic meaning of old, but each word conjures up different kinds of images about a senior adult. They embody ideas beyond factual information—they shape our conception of the person I’m describing.

This is even more true with metaphor. A metaphor is an image used to describe something else that is not actually that thing. My love is like a red rose. My love is not really a rose, but I use the image to communicate what cannot be adequately described in abstract words.

Art embodies ideas and communicates them in ways that abstract words alone cannot.

Art embodies ideas and communicates them in ways that abstract words alone cannot.

And in this very way, Scripture itself artistically embodies sound doctrine. The Bible is not an encyclopedia of doctrine or even a systematic theology—it is a collection of artistically embodied doctrine. It is filled with imagery, poetry, narrative, and other artistic devices that do absolutely communicate truth through propositions, but it also communicates embodied truth through artistic devices.

Take what is likely the most well-known metaphor in Scripture, for example: “The Lord is my shepherd.”

God is not really a man on a hillside tending to literal sheep. We all recognize that this is an image meant to shape our inner conception of who God is. David could have described God in a more detached propositional way by describing the way that God cares for his people, guides us, tends to our needs, and protects us. But instead, David chose to embody those ideas through one concise image—Shepherd. That one image embodies all of those ideas and more, ideas that would either take a whole lot more words to express or would be virtually impossible to capture with non-artistic language.

Even the most didactic portions of Scripture—New Testament epistles, for example—are filled with imagery, careful word choice, and precise syntax that don’t just tell us right doctrine, they embody right doctrine. They don’t just inform our minds, they shape our hearts, our inner conception of truth. Kevin Vanhoozer summarizes this well:

It has been said . . . that poetry is “the best words put in the best order.” Similarly, because we are dealing with the Bible as God’s Word, we have good reason to believe that the biblical words are the right words in the right order.1Kevin J. Vanhoozer, “Lost in Interpretation? Truth, Scripture, and Hermeneutics,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. 48, no. 1 (2005): 96, 100.

Leland Ryken has similarly argued throughout his career that we need to understand that the literary aspects of Scripture are essential to the truth it communicates:

The point is not simply that the Bible allows for the imagination as a form of communication. It is rather that the biblical writers and Jesus found it impossible to communicate the truth of God without using the resources of the imagination. The Bible does more than sanction the arts. It shows how indispensable they are.2Leland Ryken, “The Bible as Literature Part 4: ‘With Many Such Parables’: The Imagination as a Means of Grace,” Bibliotheca Sacra 147, no. 587 (1990): 393

Ryken argues this for exactly the issue under consideration in this article: ideas are embodied in artistic forms:

Everything that is communicated in a piece of writing is communicated through the forms in which it is embodied.3Leland Ryken, Words of Delight: A Literary Introduction to the Bible, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1993), 20.

So Scripture commands us to be reverent, and then various artistic elements in Scripture show us what reverence is like. Scripture tells us to love God, and then its artistic expressions embody appropriate love. Scripture admonishes us to be godly, and its artistic expressions form our conception of what godliness should be like.

Embodied Interpretation of Facts

Art embodies ideas because art presents an interpretation of the ideas it carries. As Ryken notes,

Artists do more than present human experience; they also interpret it from a specific perspective. Works of art make implied assertions about reality.4Leland Ryken, The Liberated Imagination: Thinking Christianly About the Arts (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2005), 171.

How so? In exactly the same way that reverence, dignity, and self-control accord with sound doctrine. Reverence is not just another way of articulating sound doctrine—reverence embodies sound doctrine; it applies sound doctrine in real life.

And in the same way, art can embody ideas. Ryken explains:

The method of art is to incarnate meaning in concrete form. The artist shows, and is never content to only tell in the form of propositions. The strategy of art is to enact rather than summarize.5Ryken, Liberated Imagination, 28.

This makes sense when we remember that art—whether we’re talking about poetry, literature, drama, or music—is itself human behavior; art is human expression. What we express through an artistic medium is not just ideas abstractly stated; rather, an artistic expression is a person’s interpretation of ideas.

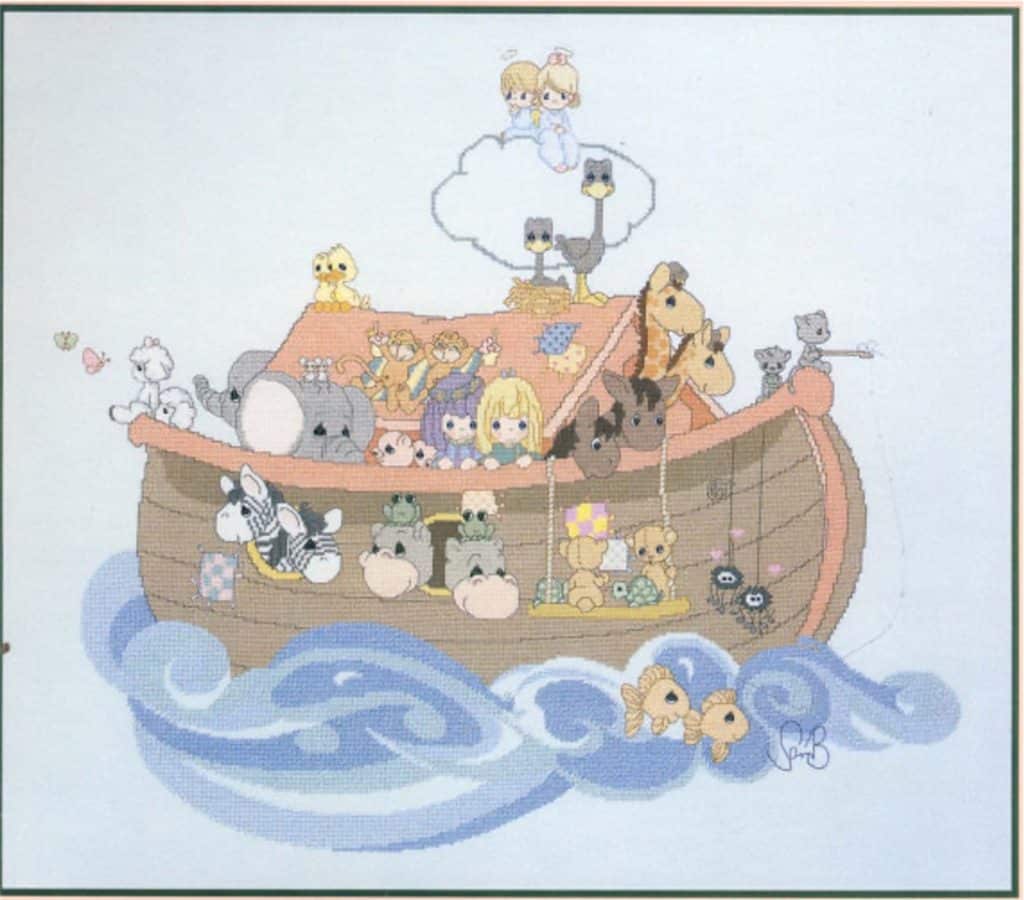

Consider, for example, the following two artistic representations of Noah and the ark. These two pictures are not just communicating facts about the biblical narrative, they embody a particular interpretation of that historical event.

Musical Embodiment

This is particularly true in music with words. The words themselves express ideas, but even the word choices, images employed, and word order already express an interpretation of those ideas.

Add music, and now the artist is further expressing interpretation of the ideas present in the lyrics.

One of the best illustrations of this is the infamous example of Marilyn Monroe singing “Happy Birthday” to President Kennedy. The words she sang were certainly not controversial, but her tone, body language, and performance style created a scandal. Notice how even Wikipedia describes the event:

“Happy Birthday, Mr. President” was a song sung by actress/singer Marilyn Monroe on Saturday, May 19, 1962, for then-President of the United States, John F. Kennedy, at a celebration for his forty-fifth birthday, ten days before the actual day of his 45th birthday, Tuesday, May 29. Sung in a sultry voice, Monroe sang the traditional “Happy Birthday to You” lyrics, with “Mr. President” inserted as Kennedy’s name. . . . Afterwards, President Kennedy came on stage and joked about the song, saying, “I can now retire from politics after having had Happy Birthday sung to me in such a sweet, wholesome way,” alluding to Monroe’s delivery, her racy dress, and her general image as a sex symbol.

In this case, the textual content and even the musical form itself were far from offensive. Yet Monroe’s vocal performance, delivery, dress, and image embodied messages that were missed by nobody.

The point is that music—in all of its complexities of melody, harmony, rhythm, instrumentation, and performance style—embodies interpretation of ideas that extend beyond merely what the words themselves express.

Music—in all of its complexities of melody, harmony, rhythm, instrumentation, and performance style—embodies interpretation of ideas that extend beyond merely what the words themselves express.

Of course, what everyone wants to know at this point is, what are the precise specifics of what makes a particular song embody a particular theology? Well, we certainly could get into specifics of music theory, acoustics, physics, and emotional resonance, but these kinds of discussions are admittedly difficult exactly because, as mentioned above, words are often too imprecise to articulate certain things. As someone once said, “Talking about music is like dancing about architecture.”

Music is actually more precise than words. As I’ve argued, it can express more nuanced interpretations of ideas than just a few words can. Again, that’s the whole point of art, to give language to interpretations and ideas that words alone would be inadequate to express. Again, this is why God used art in Scripture itself.

But this challenge doesn’t mean we cannot discern what music is expressing, anymore than our inability to describe the physiological causes of disrespectful tone of voice hinders us from recognizing it in a child. Anyone can discern disrespect, fear, anger, or dignity in another person simply by observing their facial expressions, body language, and vocal inflection.

For instance, if you ask me how I’m doing, and I answer “fine,” the way I say it embodies a certain interpretation of that word and indicates whether I’m really OK or I’m answering in a sarcastic or ironic manner. If I come home from work and ask my wife how the day went, and she answers “fine” with a grimace on her face and a sigh in her tone, I know there’s more there than what is communicated literally in that word.

The same is true for music. You don’t have to be a musician or a music theorist to be able to discern what kinds of interpretations are being made with various kinds of music. Contrary to a lot of caricatures and conjecture, this is a fairly universal phenomenon. There is vast uniformity of agreement about what various music means; since music is human expression, humans can discern what other humans are expressing because of their shared humanity.

When you’re watching a film, and the scene is people playing on the beach, but the music is sinister and menacing, you know something bad is coming. The music is presenting an interpretation of the scene that you can’t miss. This is a universal phenomenon.

So the critical question Christians must always ask about a particular artistic expression, whether literary, musical, or otherwise, is this:

Does the interpretation of reality in this work conform or fail to conform to Christian doctrine or ethics?6Ryken, Liberated Imagination, 179.

In other words, do the ideas embodied in this work of art accord with sound doctrine?

References

| 1 | Kevin J. Vanhoozer, “Lost in Interpretation? Truth, Scripture, and Hermeneutics,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. 48, no. 1 (2005): 96, 100. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Leland Ryken, “The Bible as Literature Part 4: ‘With Many Such Parables’: The Imagination as a Means of Grace,” Bibliotheca Sacra 147, no. 587 (1990): 393 |

| 3 | Leland Ryken, Words of Delight: A Literary Introduction to the Bible, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1993), 20. |

| 4 | Leland Ryken, The Liberated Imagination: Thinking Christianly About the Arts (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2005), 171. |

| 5 | Ryken, Liberated Imagination, 28. |

| 6 | Ryken, Liberated Imagination, 179. |