Here’s one of the biggest reasons I object to what has come to be called “Christian Nationalism”: we simply do not find anything like it in the New Testament.

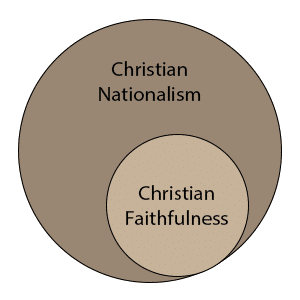

In this essay, I would like to sketch what I believe is the biblical alternative to Christian Nationalism: Christian Faithfulness. But before I do, allow me to acknowledge an inherent problem in this that I believe has led to a lot of confusion: everything about what I am going to describe as New Testament Christian Faithfulness is also part of Christian Nationalism. In other words, Christian Nationalists will read what I write here, and they will say, “I agree with that. That’s Christian Nationalism.”

But let me stress this: I agree that Christian Nationalists want Christian Faithfulness—but they want more than this. Let me try to illustrate this with a picture:

The fact is that I hate the same kinds of things happening in our culture that the Christian Nationalist hates, and I truly do appreciate the kind of Christian Faithfulness that many Christian Nationalists promote. On both of these, we agree.

But it is important to recognize that while I am about to sketch the New Testament picture of Christian Faithfulness that most (all?) Christian Nationalists would also promote, they want more than this.

What Is Christian Nationalism?

What more do they want? As I pointed out last week, Christian nationalism is the idea of a nation that explicitly considers itself to be Christian and governs itself accordingly. Stephen Wolfe’s book, The Case for Christian Nationalism has become the default standard for the idea, and here is how he defines it:

Christian nationalism is a totality of national action, consisting of civil laws and social customs, conducted by a Christian nation as a Christian nation, in order to procure for itself both earthly and heavenly good in Christ.

Christian Nationalism is, as I have noted, a desire to make a nation externally “Christian” in terms of culture and laws, because Christian nationalists believe this is what will be best for its citizens and ultimately lead its citizens to faith in Jesus Christ. On a larger scale, it is a desire to rebuild what has come to be called “Christendom,” what Doug Wilson has described as “a distinctively Christian civil order.”

The New Testament Does not Contain Anything Like Christian Nationalism

My first objection to Christian Nationalism is that it has been tried before, and every time it was tried, it failed. Furthermore, the establishment of a purely external “cultural Christianity” actually hinders the Great Commission since it creates an unregenerate nominal “Christianity.”

But my second related objection is that we simply do not find anything like what Christian Nationalists propose in the pages of the New Testament. I specifically say New Testament here because of the nature of God’s progressive revelation. Hebrews 1:1–2 succinctly summarize this important doctrine:

Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world.

All Scripture is inspired, authoritative, profitable, and sufficient, but not all in the same way. For example, are the Mosaic dietary restrictions profitable? Sure; but not in the same way as Paul’s discussion of dietary restrictions in Colossians 2. This is because God’s working out of his sovereign plan to establish his kingdom on earth is progressive, and thus the revelation he gave us in each successive administration of his plan is also progressive.

All Reformed theologians believe this, though Baptists and Presbyterians will differ slightly since Presbyterians believe that the Old and New Covenants are two administrations of one covenant (emphasizing more continuity between the OT and NT), and Baptists believe that the New Covenant is “not like” (Jer 31:32) the Old. This is why I have noted that Christian Nationalism sounds like an application of paedobaptism to nations, and thereby inherently inconsistent with Baptist theology.

The supreme specific authority for what the NT church is and how we are supposed to conduct ourselves in this stage in the outworking of God’s plan must come from the NT, particularly the Epistles. Edward Hiscox, author of the influential book on Baptist polity, New Directory of Baptist Churches, says it this way:

The New Testament is the constitution of Christianity, the charter of the Christian Church, the only authoritative code of ecclesiastical law, and the warrant and justification of all Christian institutions.1Edward T. Hiscox, New Directory of Baptist Churches (Philadelphia: Judson Press, 1894), 11.

The Pilgrim Character of the New Testament

With this in mind, what is the overarching character of the NT’s instructions regarding how we ought to be living in this age? The apostle Peter summarizes it well in 1 Peter 1:17:

And if you call on him as Father who judges impartially according to each one’s deeds, conduct yourselves with fear throughout the time of your exile.

As believers in Jesus Christ, “our citizenship is in heaven” (Phil 3:20). We are “citizens with the saints and members of the household of God” (Eph 2:19), and as such, we are set apart from the unbelieving people of this world (Jn 15:19; 17:14, 16). Jesus said that this world hates him, because he “testif[ies] about it that its works are evil” (Jn 7:7). Galatians 1:4 calls this world the “present evil age.” Second Corinthians 4:4 identifies the “god of this world” as one who has “blinded the minds of the unbelievers, to keep them from seeing the light of the gospel of the glory of Christ,” this one who Ephesians 2:2 calls “the prince of the power of the air, the spirit that is now at work in the sons of disobedience.”

This is why Peter describes our current situation as “the time of your exile” (1 Pet 1:17) and specifically calls us “sojourners and exiles” (1 Pet 2:11). John commands Christians, “Do not love the world or the things in the world” (1 Jn 2:15), and Paul insists that Christians “do not be conformed to this world” (Rom 12:2).

Christians in the first through third centuries recognized this. They couldn’t help but recognize their status as exiles because they were increasingly persecuted for their faith. Yet in 313, the Roman emperor Constantine legalized Christianity, and God’s people forgot they were sojourners and exiles. And then in 392, emperor Theodosius declared Christianity to be the established religion of the Roman empire and outlawed all other religions. In essence, the church and state eventually united, forming what many call “Christendom,” and church leaders literally wanted to turn the empire into a theocracy like Israel, climaxing in the Holy Roman Empire. This very quickly created a lot of nominal Christianity, lulling true Christians into forgetting that they were exiles.

The Reformers, especially Luther and Calvin, argued against the church/state union by articulating a two kingdom theology, but they were unable to completely disentangle themselves from socio-political ties during their lives. The Church of England especially, as their name indicates, maintained a close union between Church and state. It really wasn’t until the early Baptists in England, and a few groups prior to Baptists, that we find a clear articulation of the need to recover a separation between church and state—a Baptist distinctive. This emphasis of the separation of church and state influenced the founding of the United States of America as well, but nevertheless, the effects of Christendom can still be observed today, for good and for ill.

How many Christians today consider themselves sojourners and exiles? How many Christians recognize that their citizenship is in another kingdom and that they are currently living in a world hostile to them and their way of life? How many Christians consider themselves distinct from the unbelieving people around them?

Resident Aliens

Yet this is not the complete picture of the Christian situation. The presence of sin in the world does not entirely destroy the image of God in unbelieving people, and the promises God made to Noah that he would continue to preserve order through the institutions he established are still in effect. Even though Satan is the “god of this world,” God is still on the throne of his Universal Kingdom, and he is still preserving his creation through human governments and other God-ordained human institutions. Thus even unbelievers, when they act consistent with that order, can do what God has blessed them to do—they can preserve order and justice in the world, they devise successful political systems, they can produce worthy art, and they can teach things that are true. These are not “neutral” things; rather, in cases like this, pagans are simply doing “what the law requires” since “the law is written on their hearts” (Rom 2:14–15).

And so, in these kinds of activities, God’s people can stand alongside unbelieving people, participating in and contributing to society as citizens of the universal common kingdom of God. A perfect illustration of this is what the prophet Jeremiah says to Israel in Babylonian exile, a situation for Israel analogous to the church’s situation in this age:

Thus says the Lord of hosts, the God of Israel, to all the exiles whom I have sent into exile from Jerusalem to Babylon: 5 Build houses and live in them; plant gardens and eat their produce. 6 Take wives and have sons and daughters; take wives for your sons, and give your daughters in marriage, that they may bear sons and daughters; multiply there, and do not decrease. 7 But seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, and pray to the Lord on its behalf, for in its welfare you will find your welfare. (Jeremiah 29:4-7)

Israel in exile experienced a stark antithesis between their religion and the religion of their captors—they sat down and wept as their captors mocked them when they gathered by waters of Babylon to worship, and yet they were able to share commonality with their captors as well.

The same is true for the church. Jesus was clear: Render to Caesar that which is Caesar’s. Why? Because the welfare of the city is also our welfare. A healthy government that protects the innocent and punishes injustice is part of God’s universal reign, even if that government is pagan. In the context of teaching Christians how to live as sojourners and exiles, Peter specifically says that Christians should submit to earthly authorities and even honor them (1 Pet 2:13–18). Why? Because the welfare of the city is also our welfare. Government was instituted by God himself, and inasmuch as governing officials rule with equity and justice, they are doing exactly what God intends for them to do. Like Jeremiah, Paul commands that “supplications, prayers, intercessions, and thanksgivings be made for all people, for kings and all who are in high positions” (1 Tim 2:1–2). Why? So that “we may lead a peaceful and quite life, godly and dignified in every way,” exactly why God established human government in Genesis 9.

There is a real sense in which Christians, analogous to Israel in exile, are dual citizens—resident aliens. Christians are first and foremost citizens of the redemptive kingdom, but they are also citizens of God’s Universal common Kingdom along with every other human being. And thus, Christians contribute to society, submit to and pray for governmental authorities, and participate in various aspects of cultural endeavors, as long as they reflect and remain consistent with God’s law.

Christian Faithfulness

In other words, the overarching character of the New Testament’s description of Christians is as God’s unique people, citizens of a heavenly kingdom, who currently live in the kingdoms of men as resident aliens. We are in this world—God has left us here for a purpose, but in reality, this world is not our home; we’re just passing through. We are sojourners and exiles.

The New Testament prescribes Christian Faithfulness, not Christian Nationalism.

But this very character ought to affect how we live while we are here. Everything about how we live in society and interact in culture must flow out of our ultimate citizenship. There is no divorcing of the sacred and “secular” for the Christian in this sense. We cannot simply say, “Well, I’m saved, heaven is my true home, Christ is going to come back one day and defeat all of his enemies, and so really nothing I do in this life really matters. Our mission as the church is to make disciples, so we ought to just preach the gospel and go to church and not really care about anything that happens in this world.”

Wrong. The emphasis of the NT is that, in light of the fact that your citizenship is in Christ’s redemptive kingdom, in light of the fact that you are a holy nation, a people for God’s own possession, you must live in a certain way in the kingdoms of this world.

So how ought we to live as sojourners and exiles?

First, the Bible commands Christians to live holy lives:

But as he who called you is holy, you also be holy in all your conduct.

1 Pet 1:15

Second, the Bible gives specific commands regarding how Christians should live in their various human vocations such as husbands, wives, parents, children, employers, and employees (Eph 5:15–6:9; Col 3:18–4:6; 1 Pet 2:18–20). Raising godly children matters. For the glory of God, the salvation and sanctification of our own children and others around us, and for the benefit of society in general, it matters how husbands lead and how wives submit, it matters how we discipline our children, it matters how we educate our children. Don’t underestimate the deep importance of rearing godly children.

Our human vocations matter. When we work hard to produce goods and services that are helpful to our fellow man, we are doing what God intended to help preserve peace and prosperity in the common kingdoms of this world. That is worthy work because it is what God intended work to be.

Third, all Christians have some responsibilities toward society, such as submitting to governmental authority when they fulfill their role in preserving civil order (Rom 13:1–10; 1 Pet 2:13–17) and rendering to Caesar what is Caesar’s (Matt 22:21). The human institution of government is God’s institution, which God established to sustain humanity in a sin-cursed world. We ought to fervently pray for government authority, “that we may live a peaceful and quiet life, godly and dignified in every way” (2 Tim 2:1–2).

Further, since we enjoy a constitutional republic today, “honoring the emperor” (1 Peter 2:17) means to uphold the Constitution. It’s not perfect, but the emperor in Peter’s day was not perfect, either, to say the least. Our political situation is far better than what Peter’s audience had. We have the privilege of participation in our governmental system that Peter’s audience did not have. So in our situation, to honor the emperor means to vote, to be active in the political system, seeking to support candidates whose political policies will best accomplish what God has appointed as the purpose of government.

We can’t just sit back and say, “We’re citizens of another kingdom; so politics don’t matter.” No, because we are citizens of another kingdom, we must honor the emperor that our King appointed. So vote, stand for morality in our society, and be active in the political process for God’s glory and, as Peter says in verse 17, for the honor of everyone and the love of the brotherhood.

Fourth, Christians should recognize how their beliefs, relationship with God, and citizenship in heaven necessarily affect other aspects of human life in society. We ought to apply our Christian values to every aspect of our lives. All of Christ for all of life. We ought to “do good unto all men” (Gal 6:10), and this ought to affect all of our interactions with our fellow men. Peter urges us to “have unity of mind, sympathy, brotherly love, a tender heart, and a humble mind. Do not repay evil for evil or reviling for reviling, but on the contrary, bless, for to this you were called, that you may obtain a blessing” (1 Pet 3:8–9). We ought to strive to “live peaceably with all” (Rom 12:18) and “lead a peaceful and quiet life, godly and dignified in every way.”

We ought to apply our Christian values to every aspect of our lives. All of Christ for all of life.

Finally, part of the motivation given in Scripture for Christians living good lives in the world is witness. This is behind Christ’s description of his followers as “the light of the world.” He admonishes us, “Let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven” (Matt 5:14–16).

And this, then, fits directly with the unique mission that has been given to Christ’s churches during this present age:

Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

Matt 28:19–20

Where is Christian Nationalism?

Put simply, the New Testament prescribes Christian Faithfulness, not Christian Nationalism. As I noted at the beginning, Christian Nationalists want Christian Faithfulness, but they want more than that.

Where in the New Testament do we find anything like building Christendom? Where do we find anything like pursuing full nations explicitly referring to themselves as Christian? Where do we find anything like pursuing a civil order modeled after Old Testament Israel? Where do you see anything like the pursuit of establishing Christianity as the established religion of a nation? Surely if this were God’s intent for us, we would see even a hint of it in the New Testament epistles.

I understand the broader biblical/theological argument set forth by Christian Nationalists and/or Postmillennialists, and I do believe in the importance of systematic theology. But if God wanted us to establish nations that explicitly designate themselves as “Christian,” you would think we’d find even the slightest hint of it in the New Testament epistles.

But we don’t. What we find is an emphasis upon the fact that Christians are citizens of a heavenly kingdom, that we are pilgrims in this present world, but that we should care about this world nonetheless.

Christian Nationalism? No.

Christian Faithfulness? Yes.

References

| 1 | Edward T. Hiscox, New Directory of Baptist Churches (Philadelphia: Judson Press, 1894), 11. |

|---|